Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-11

Introduction | Index | Marvels | Books | People | Establishments | Freedom Fighter | Image Gallery | Video

This website is under construction please visit our Hindi website "HI.BRAJDISCOVERY.ORG"

|

<sidebar>

__NORICHEDITOR__

</sidebar> | |||||||

|

Mathura A District Memoir By F.S.Growse

|

AT a distance of three miles from the city of Mathura, the road to Gobar dhan runs through the village of Satoha, by the side of a large tank of very sacred repute, called Santanu Kund. The name commemorates a Raja Santanu who (as is said 'on the spot) here practised, through a long course of years, the severest religious austerities in the hope of obtaining a son. His wishes were at last gratified by a union with the goddess Ganga, who bore him Bhishma, one of the famous heroes of the Mahabharat. Every Sunday the place is frequented by women who are desirous of issue, and a large fair is held there on the 6th of the light fortnight of Bhadon. The tank, which is of very considerable dimensions, was faced all round with stone, early last century, by Sawai Jay Sinh of Amber, but a great part of the masonry is now much dilapidated. In its centre is a high hill connected with the main land by a bridge. The sides of the island are covered with fine ritha trees, and on the summit, which is approached by a flight of fifty stone steps, is a small temple. Here it is incum bent upon the female devotees, who would have their prayers effectual, to make some offering to the shrine, and inscribe on the ground or wall the mystic device called in Sanskrit Svastika and in Hindi Sathiya, the fylfot of Western eccle siology. The local superstition is probably not a little confirmed by the acci dental resemblance that the king's name bears to the Sanskrit word for ‘children,’ santana. For, though Raja Santanu is a mythological personage of much ancient celebrity, being mentioned not only in several of the Puranas, but also in one of the hymns of the Rig Veda, he is not much known at the present day, and what is told of him at Satoha is a very confused jumble of the original legend. The signal and, according to Hindu ideas, absolutely fearful abnegation of self, there ascribed to the father, was undergone for his gratification by the dutiful son, who thence derived his name of Bhishma, ‘the fearful.’ For, in extreme old age, the Raja was anxious to wed again, but the parents of the fair girl on whom he fixed his affections would not consent to the union, since the fruit of the marriage would be debarred by Bhishma's seniority from the succession to the throne. The difficulty was removed by Bhishma's filial devotion, who took an oath to renounce his birthright and never to beget a son to revive the claim. Hence every religious Hindu accounts it a duty to make him amends for this want of direct descendants by once a year offering libations to Bhishma's spirit in the same way as to one of his own ancestors. The formula to be used is as follows:—" I present this water to the childless hero, Bhishma, of the race of Vyaghrapada, the chief of the house of Sankriti. May Bhishma, the son of Santanu, the speaker of truth and subjugator of his passions, obtain by this water the oblations due from sons and grandsons."

The story in the Nirukta Vedanga relates to an earlier period in the king's life, if, indeed, it refers to the same personage at all, which has been doubted. It is there recorded that, on his father's death, Santanu took possession of the throne, though he had an elder brother, by name Devapi, living. This violation of the right of primogeniture caused the land to be afflicted with a drought of twelve years' continuance, which was only terminated by the recita tion of a hymn of prayer (Rig Veda, x., 98) composed by Devapi himself, who had voluntarily adopted the life of a religious. The name Satoha is absurdly derived by the Brahmans of the place from sattu, ' bran,' which is said to have been the royal ascetic's only diet. In all probability it is formed from the word Santanu itself, combined with some locative affix, such as sthana.

Ten miles further to the west is the famous place of Hindu pilgrimage, Gobardhan, i.e., according to the literal meaning of the Sanskrit compound, the nurse of cattle.' The town, which is of considerable size, with a population of 4,944, occupies a break in a narrow range of hill, which rises abruptly from the alluvial plain, and stretches in a south-easterly direction for a distance of some four or five miles, with an average elevation of about 100 feet.

This is the hill which Krishna is fabled to have held aloft on the tip of his finger for seven days and nights to cover the people of Braj from the storms poured down upon them by Indra when deprived of his wonted sacrifices. In pictorial representations it always appears as an isolated conical peak, which is as unlike the reality as possible. It is ordinarily styled by Hindus of the present day the Giri-raj, or royal hill, but in earlier literature is more frequently designated the Anna-kut. There is a firm belief in the neighbourhood that, as the waters of the Jamuna are yearly decreasing in body, so too the sacred hill is steadily diminishing in height; for in past times it was visible from Aring, a town four or five miles distant, whereas now a few hundred yards are sufficient to remove it from sight. It may be hoped that the marvellous fact reconciles the credulous pilgrim to the insignificant appearance presented by the object of his adoration. It is accounted so holy that not a particle of the stone is allowed to be taken for any building purpose; and even the road which crosses it at its lowest point, where only a few fragments of the rock crop up above the ground, had to be carried over them by a paved causeway.

The ridge attains its greatest elevation towards the south between the vil lages of Jati pura and Anyor. Here, on the submit, was an ancient temple founded in the year 1520 A. D., by the famous Vallabhacharya of Gokul, and dedicated to Sri-nath. In anticipation of one of Aurangzeb's raids, the image of the god was removed to Nathdwara in Udaypur territory, and has remained there ever since. The temple on the Giri-raj was thus allowed to fall into ruin, and the wide walled enclosure now exhibits only long lines of foundations and steep flights of steps, with a small, uutenanted, and quite modern shine. The plateau, however, commands a very extensive view of the neighbouring coun ty, both on the Mathura and the Bharatpur side, with the fort of Dig and the heights of Nand-ganw and Barsana in the distance.

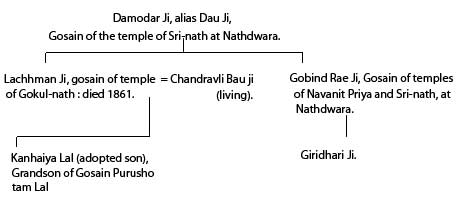

At the foot of the hill on one side is the little village of Jatipura with several temples, of which one, dedicated to Gokul-nath, though a very mean building in appearance, has considerable local celebrity. Its head is the Gosain of the temple with the same title at Gokul, and it is the annual scene of two religious solemnities, both celebrated on the day after the Dip-dan at Gobardhan. The first is the adoration of the sacred hill, called the Giri-raj Puja, and the second the Anna-Kut, or commemoration of Krishna's sacrifice. They are always accompanied by the renewal of a long-standing dispute be tween the priests of the two rival temples of Sri-nath and Gokul-nath, the one of whom supplies the god, the other his shrine. The image of Gokul-nath, the traditional object of veneration, is brought over for the occasion from Gokul, and throughout the festival is kept in the Gokul-nath temple on the hill, except for a few hours on the morning after the Diwali, when it is exposed for worship on a separate pavilion. This building is the property of Giridhari Ji, the Sri-nath Gosain, who invariably protests against the intrusion. Party-feeling runs so high that it is generally found desirable a little before the anniversary to take heavy security from the principals on either side that there shall be no breach of the peace. The relationship between the Gosains is explained by the following table:—

Immediately opposite Jatipura, and only parted from it by the intervening range, is the village of Anyor—literally ‘the other side’—with the temple of Sri-nath on the summit between them. A little distance beyond both is the village of Puchhri, which, as the name denotes, is considered the ' extreme limit' of the Giri-raj.

Kartik, the month in which most of Krishna's exploits are believed to have been performed, is the favorite time for the pari-krama, or ‘perambulation’ of the sacred hill. The dusty circular road which winds around its base has a length of seven kos, that is, about twelve miles, and is frequently measured by devotees who at every step prostrate themselves at full length. When flat on the ground, they mark a line in the sand as far as their hands can reach, then rising they prostrate themselves again from the line so marked, and continue in the same style till the whole weary circuit has been accomplished. This ceremony, called Dandavati pari-krama, occupies from a week to a fortnight, and is generally performed for wealthy sinners vicariously by the Brahmans of the place, who receive from Rs. 50 to Rs. 100 for their trouble and transfer all the merit of the act to their employers. The ceremony has been performed with a hundred and eight. [1] prostrations at each step (that being the number of Radha's names and of the beads in a Vaishnava rosary), it then occupied some two years, and was remunerated by a donation of Rs. 1,000.

About the centre of the range stands the town of Gobardhan on the margin of a very large irregularly shaped masonry tank, called the Manasi Ganga, supposed to have been called into existence by the mere action of the divine will (manasa). At one end the boundary is formed by the jutting crags of the holy hill; on all other sides the water is approached by long flights of stone steps. It has frequently been repaired at great cost by the Rajas of Bharat-pur; but is said to have been originally constructed in its present form by Raja Man Sinh of Jaypur, whose father built the adjoining temple of Harideva. There is also at Banaras a tank constructed by Man Sinh, called Man Sarovar, and by it a temple dedicated to Manesvar: facts which suggest a suspicion that the name ‘Manasi’ [2] is of much less antiquity than is popularly believed. Unfortunately, there is neither a natural spring, nor any constant artificial supply of water, and for half the year the tank is always dry. But ordinarily at the annual illumination, or Dip-dan, which occurs soon after the close of the rains, during the festival of the Diwali, a fine broad sheet of water reflects the light of the innumerable lamps, which are ranged tier above tier along the ghats and adjacent buildings, by the hundred thousand pilgrims with whom the town is then crowded.

In the year 1871, as there was no heavy rain towards the. end of the season, and the festival of the Diwali also fell later than usual, it so happened that on the bathing day, the 12th of November, the tank was entirely dry, with the exception of two or three green and muddy little puddles. To obviate this mischance, several holes were made and wells sunk in the area of the tank, with one large pit, some 30 feet square and as many deep, in whose turbid waters many thousand pilgrims had the happiness of immersing themselves. For several hours no less than twenty-five persons a minute continued to descend, and as many to ascend, the steep and slippery steps; while the yet more fetid patches of mud and water in other parts of the basin were quite as densely crowded. At night, the vast amphitheatre, dotted with groups of people and glimmering circles of light, presented a no less picturesque appearance than in previous years when it was a brimming lake. To the spectator from the garden side of the broad and deep expanse, as the line of demarkation between the steep flights of steps and the irregular masses of building which immediately sur mount them ceased to be perceptible, the town presented the perfect semblance of a long and lofty mountain range dotted with fire-lit villages; while the clash of cymbals, the beat of drums, the occasional toll of bells from the adjoining temples, with the sudden and long-sustained cry of some enthusiastic band, vociferating the praises of mother Ganga, the clapping of hands that began scarce heard, but was quickly caught up and passed on from tier to tier, and prolonged into a wild tumult of applause,—all blended with the ceaseless mur mur of the stirring crowd in a not discordant medley of exciting sound. Accord ing to popular belief, the ill-omened drying up of the water, which had not occurred before in the memory of man, was the result of the curse of one Habib-ullah Shah, a Muhammadan fakir. He had built himself a hut on the top of the Giri-raj, to the annoyance of the priests of the neighbouring temple of Dan-Rae, who complained that the holy ground was defiled by the bones and other fragments of his unclean diet, and procured an order from the Civil Court for his ejectment. Thereupon the fakir disappeared, leaving a curse upon his persecutors; and this bore fruit in the drying up of the healing waters of the Manasi Ganga.

Close by is the famous temple of Hari-deva, erected during the tolerant reign of Akbar by Raja Bhagawan Das of Amber on a site long previously occupied by a succession of humbler fanes. It consists of a nave 68 feet in length and 20 feet broad, leading to a choir 20 feet square, with a sacrarium of about the same dimensions beyond. The nave has four openings on either side, of which three have arched heads, while the fourth nearest the door is covered by a square architrave supported by Hindu brackets. There are clerestory windows above, and the height is about 30 feet to the cornice, which is decorated at intervals with large projecting heads of elephants and sea-monsters. There was a double roof, each entirely of stone: the outer one a high pitched gable, the inner an arched ceiling, or rather the nearest approach to an arch ever seen in Hindu design. The centre was really flat, but it was so deeply coved at the sides that, the width of the building being inconsiderable, it had all the effect of a vault, and no doubt suggested the possibility of the true radiating vault, which we find in the temple of Govind Deva built by Bhagawan's son and successor, Man Sinh at Brinda-ban. The construction is extremely massive, and even the exterior is still solemn and imposing, though the two towers which originally crowned the choir and sacrarium were long ago levelled with the roof of the nave. The material employed throughout the superstructure is red sandstone from the Bharatpur quarries, while the foundations are composed of rough blocks of the stone found in the neighbourhood. These have been laid bare to the depth of several feet; and a large deposit of earth all round the basement would much enhance the appearance as well as the stability of the building.

Bihari Mall, the father of the reputed founder, was the first Rajput who attached himself to the court of a Muhammandan emperor. He was chief of the Rajawat branch of the Kanchhwaha Thakurs seated at Amber, and claimed to be eighteenth in descent from the founder of the family. The capital was subsequently transferred to Jaypur in 1728 A.D.; the present Maharaja being the thirty-fourth descendant of the original stock. In the battle of Sarnal, Bhagawan Das had the good fortune to save Akbar's life, and was subsequently appointed Governor of the Panjab. He died about the year 1590 at Lahor. His daughter was married to prince Salim, who eventually became emperor under the title of Jahargir; the fruit of their marriage being the unfortunate prince Khusru.

The temple has a yearly income of some Rs. 2,300, derived from the two villages, Bhagosa and Lodhipuri, the latter estate being a recent grant, in lien of an annual money donation of Rs. 500, on the part of the Raja of Bharat-pur, who further makes a fixed monthly offering to the shrine at the rate of one rupee per diem. The hereditary Gosains have long devoted the entire income to their own private uses, completely neglecting the fabric of the temple and its religious services.’ [3] In consequence of such short-sighted greed, the votive offerings at this, one of the most famous shrines in Upper India, have dwindled down to about Rs. 50 a year. Not only so, but, early in 1872, the roof of the nave, which had hitherto been quite perfect, began to give way. An attempt was made by the writer of this memoir to procure an order from the Civil Court authorizing the expenditure, on the repair of the fabric, of the proceeds of the temple estate, which, in consequence of the dispute among the shareholders, had for some months past been paid as a deposit into the district treasury and had accumulated to more than Rs. 3,000. There was no unwillingness on the part of the local Government to further the proposal, and an engineer was deputed to examine and report on the probable cost. But an unfortunate delay occurred in the Commissioner's office, the channel of correspondence, and meanwhile the whole of the roof fell in, with the exception of one compartment. This, however, would have been sufficient to serve as a model in the work of restora tion. The estimate was made out for Rs. 8,767; and as there was a good balance in hand to begin upon, operations might have been commenced at once and completed without any difficulty in the course of two or three years. But no further orders were communicated by the superior authorities from April, when the estimate was submitted, till the following October, and in the interim a baniya from the neighbouring town of Aring, by name Chhitar Mall, hoping to immortalise himself at a moderate outlay, came to the relief of the temple proprietors and undertook to do all that was necessary at his own private cost. He accordingly ruthlessly demolished all that yet remained of the original roof, breaking down at the same time not a little of the curious cornice, and in its place simply threw across, from wall to wall, rough and unshapen wooden beams, of which the best that can be said is, that they may, for some few years, serve as a protection' from the weather. But all that was unique and characteristic in the design has ceased to exist; and thus another of the few pages in the fragmentary annals of Indian architecture has been blotted out for ever. Like the temple of Gobind Deva at Brinda-ban, it has none of the coarse figure sculpture which detract so largely from the artistic appearance of most Hindu religious buildings; and though originally consecrated to idolatrous worship, it was in all points of construction equally well adapted for the public ceremonial of the purest faith. Had it been preserved as a national monument, it might at some day, in the future golden age, have been to Gobardhan what the Pagan Pantheon is now to Christian Rome.

On the opposite side of the Manasi Ganga are two stately cenotaphs, or chhattris, to the memory of Randhir Sinh and Baladeva Sinh, Rajas of Bharat pur. Both are of similiar design, consisting of a lofty and substantial square masonry terrace with corner kiosks and lateral alcoves, and in the centre the monument itself, still further raised on a richly decorated plinth. The cells, enclosed in a colonnade of five open arches on each side, is a square apartment surmounted by a dome, and having each wall divided into three bays, of which one is left for the doorway, and the remainder are filled in with reticulated tracery. The cloister has a small dome at each corner and the curious curvi linear roof, distinctive of the style, over the central compartments. In the Iarger monument, the visitor's attention is specially directed to the panels of the doors, painted in miniature with scenes from the life of Krishna, and to the cornice, a flowered design of some vitreous material executed at Delhi. This commemorates Baladeva Sinh, who died in 1825, and was erected by his son and successor the late Raja Balavant Sinh, who was placed on the throne after the reduction of the fort of Bharat-pur by Lord Combermere in 1826. The British army figures conspicuously in the paintings on the ceilings of the pavilions. [4] Raja Randhir Sinh, who is commemorated by the companion monument, was the elder brother and predecessor of Baladeva, and died in the year 1823. These chhattris are very elegantly grouped piles of building and have an extremely picturesque effect, which is heightened by the sheet of water in front of them. But from a purely architectural point of view, they are not of any great merit, and give the idea of having been executed by a contractor, who scamped the work to increase his own profit. The decorative details are mostly poor in themeselves, and are repeated with a monotonous uniformity, which contrasts most disagreeably with the rich variety of design that distin guishes all the more important buildings either in Mathura or Brinda-ban. The painting on the interior of the domes is also as heavy and tasteless as Hindu attempts at pictorial art generally are.

A mile or so from the town, on the borders of the parish of Radha-kund, is a much more magnificent architectural group erected by Jawahir Singh in honour of his father Suraj Mall, the founder of the family, who met his death at Delhi in 1764 (see page 40). The principal tomb, which is 57 feet square, is of precisely the same style as the two already described. The best part of the design is the plinth, which is at once bold in outline and delicate in finish. With that curious blindness to practical requirements, which appears to have characterised the Hindu architect from the earliest period to the present, the decorated panels have been continued all round the four sides of the building, without a blank space being left anywhere for the steps, which the height from the ground renders absolutely necessary. The Raja's monument is flanked on either side by one of somewhat less dimensions, commemorating his two queens, Hansiya [5] and Kishori. The lofty terrace upon which they stand is 460 feet in length, with a long shallow pavilion serving as a screen at each end, and nine two-storied kiosks of varied outline to relieve the front. Attached to Rani Hansiya's monument is a smaller one in commemoration of a faithful attendant. Behind is an extensive garden, and in front, at the foot of the terrace, is an artificial lake, called the Kusum-Sarovar, 460 feet square; the flights of stone steps on each side being broken into one central and four small er side compartments by panelled and arcaded walls running out 60 feet into the water. On the north side, some progress had been made in the erection of a chhattri for Jawahir Singh, when the work was interrupted by Muhammadan inroad and never renewed. On the same side, the ghats of the lake are partly in ruins, and it is said were reduced to this condition, a very few years after their completion, by the Gosain Himmat Bahadur, who carried away the ma terials to Brindaban, to be used in the construction of a ghat which still com memorates his name there. Such a wanton exercise of power seems a little startling, and therefore it will not be out of place to explain a little in detail who this warlike Gosain was. A native of Bundel-khand, he became a pupil of Mahant Rajendra Giri, who had seceded from the Dasnamis [6] or followers of Sankaracharya, the most fanatical of all Hindu sectaries, and had joined the Saiva Nagas, a community characterized by equal turbulence unfettered by even a pretence of any religious motive. Through his instigations, Ali Baha dur, an illegitimate grandson of Baji Rao, the first Peshwa, was induced to take up arms against Sindhia and establish himself in Bundel-khand as virtually an independent sovereign. In 1802, All Bahadur fell at the siege of Kalanjar, leaving a son, Shamaher Bahadur. At first the heir was supported by Himmat, who, however, continued quietly to extend his own influence as far as possible; and, on the combination of the Mahratta chiefs against the British Government, in which they were joined by Shamsher, foreseeing in their success an immediate diminution of his own authority, he determined to co-operate with the British. On the 4th of September, 1803, a treaty was concluded between Lord Wellesley and ' Anup-giri Himmat Bahadur,' by which nearly all the territory on the west bank of the Jamuna from Kalpi to Allahabad was assigned to him. His death, however, occurred in the follow ing year, when the lands were resumed and pensions in lieu thereof granted to his family.

Other sacred spots in the town of Gobardhan are the temple of Chak resvar Mahadeva, and four ponds called respectively Go-rochan, Dharm-rochan, Pap-mochan, and Rin-mochan. But these latter, even in the rains, are mere puddles, and all the rest of the year are quite dry; while the former, in spite of its sanctity, is as mean a little building as it is possible to conceive.

The break in the hill, traversed by the road from Mathura to Dig, is called the Dan Ghat, and is supposed to be the spot where Krishna lay in wait to intercept the Gopis and levy a toll (dan) on the milk they were bringing into the town. A Brahman still sits at the receipt of custom, and extracts a copper coin or two from the passers-by. On the ridge overlooking the ghat stands the temple of Dan Rae.

For many years past one of the most curious sights of the place has been an aged Hindu ascetic, who had bound himself by a vow of absolute silence. Whatever the hour of the day, or time of the year, or however long the inter val that might have elapsed since a previous visit, a stranger was sure to find him sitting exactly on the same spot and in the same position, as if he had never once stirred; a slight awning suspended over his head, and immediately in front of him a miniature shrine containing an emblem of the god. The half century, which was the limit of his vow, has at length expired; but his tongue, bound for so many years, has now lost the power of uttering any articulate sound. In a little dog-kennel at the side sits another devotee, with his legs crossed under him, ready to enter into conversation with all corners, and looking one of the happiest and most contented of mortals; though the cell in which he has immured himself is so confined that he can neither stand up nor lie down in it.

Subsequently to the cession by Sindhia in 1803, Gobardhan was granted, free of assessment, to Kuar Lachhman Sinh, youngest son of Raja Ranjit Sinh of Bharat-pur; but on his death, in 1826, it was resumed by the Government and annexed to the district of Agra. Of late years, the paramount power has been repeatedly solicited by the Bharat-pur Raja to cede it to him in exchange for other territory of equal value. It contains so many memorials of his ances tors that the request is a very natural one for him to make, and it must be admitted that the Bharat-pur frontier stands greatly in need of rectification. It would, however, be most impolitic for the Government to make the desired concession, and thereby lose all control over a place so important, both from its position and its associations, as Gobardhan.

The following legend in the Harivansa (cap. 94) must be taken to refer to the foundation of the town, though apparently it has never hitherto been noticed in that connection. Among the descendants of Ikshvaku, who reigned at Ayodhya, was Haryasva, who took to wife Madhumati, the daughter of the giant Madhu. Being expelled from the throne by his elder brother, the king fled for refuge to the court of his father-in-law, who received him most affec tionately and ceded him the whole of his dominions, excepting only the capital Madhuvana, which he reserved for his son Lavana. Thereupon, Haryasva built, on the sacred Girivara, a new royal residence, and consolidated the king dom of Anarta, to which he subsequently annexed the country of Arupa, or (as it is otherwise and preferably read) Anupa. The third in descent from Yadu, the son and successor of Haryasva, was Bhima, in whose reign Rama, the then sovereign of Ayodhya, commissioned Satrughna to destroy Lavana's fort of Madhuvana and erect in its stead the town of Mathura. After the departure of its founder, Mathura was annexed by Bhima, and continued in the posses sion of his descendants down to Vasudeva. The most important lines in the text run thus:-

Haryasvascha mahateja divye Girivarottame

Nivesayamasa puram vasartham amaropamah Anartam nama tadrashtram surishtram Godhanayutam.

Achirenaiva kalena samriddham pratyapadyata Anupa-vishayam chaiva vela-vans-vibhushitam.

From the occurrence of the words Girivara and Godhana and the declared proximity to Mathura, it is clear that the capital of Haryasva must have been situate on the Giri-raj of Gobardhan; and it is probable that the country of Anupa was to some extent identical with the more modern Bray. Anupa is once mentioned, in an earlier canto of the poem, as having been bestowed by king Prithu on the bard Suta. The name Anarta occurs also in canto X., where it is stated to have been settled by king Reva, the son of Saryati, who made Kusasthali its capital. In the Ramayana, IV., 43, it is described as a western region on the sea-coast, or at all events in that direction, and has therefore been identified with Gujarat. Thus there would seem to have been an in timate connection between Gujarat and Mathura, long anterior to Krishna's foundation of Dwarka.

BARSANA AND NAND-GANW [7]

Barsana—population 2,773-according to modern Hindu belief the home of Krishna's favourite mistress Radha, is a town which enjoyed a brief period of great prosperity about the middle of last century. It is built at the foot and on the slope of a ridge, originally dedicated to the god Brahma, which rises abruptly from the plain, near the Bharat-pur border of the Chhata pargana, to a height of some 200 feet at its extreme point, and runs in a south-westerly direction for about a quarter of a mile. Its summit is crowned by a series of temples in honour of Larli-Ji, a local title of Radha, meaning ‘the beloved.’ These were all erected at intervals within the last two hundred years, and now form a connected mass of building with a lofty wall enclosing the court in which they stand. Each of the successive shrines was on a somewhat grander scale than its predecessor, and was for a time honoured with the presence of the divinity; but even the last and largest, in which she is now enthroned, is an edifice of no special pretension; through seated, as it is, on the very brow of the rock, and seen in conjunction with the earlier buildings, it forms an imposing feature in the landscape to the spectator from the plain below. A long flight of stone steps, broken about half way by a temple in honour of Radha's grand-father, Mahi-ban, leads down from the summit to the foot of the hill, where are two other small temples. One of them is dedicated to Radha's female com panions, called the Sakhis, who are eight in number, as follows: Lalita, Visakha, Champaka-lata, Ranga-devi, Chitra-lekha, Dulekha, Sudevi, and Chandravali. The other contains a life-size image of the mythical Brikh-bhan robed in appro priate costume and supported on the one side by his daughter Radha, and on the other by Sridama, a Pauranik character, here for the nonce represented as her brother.

The town consists almost entirely of magnificent mansions all in ruins, and lofty but crumbling walls now enclosing vast, desolate, dusty areas, which once were busy courts and markets or secluded pleasure grounds. All date from the time of Rup Ram, a Katara Brahman, who, having acquired great reputa tion as a Pandit in the earlier part of last century, became Purohit to Bharat-pur,Sindhia [8] and Holkar, and was enriched by those princes with the most lavish donations, the whole of which he appears to have expended on the embellishment of Barsana and the other sacred places within the limits of Braj, hie native country. Before his time, Barsana, if inhabited at all, was a men hamlet of the adjoining village Ucha-ganw, which now, under its Gujar landlords, is a mean and miserable place, though it boasts the remains of a fort and an ancient and well-endowed temple, dedicated to Baladeva. Rup Ram was the founder of one of the now superseded temples of Larli Ji, with the stone staircase up the side of the hill. He also constructed the largest market-place in the town, with as many, is it said, as sixty-four walled gardens; a princely mansion for his own residence; several small temples and chapels, and other courts and pavilions. One of the latter, a handsome arcaded building of carved stone, has for some years past been occupied by the Government as a police-station without any payment of rent or award of compensation, though the present representative of the family is living on the spot and is an absolute pauper. Three cenotaphs commemorating Rup Ram himself and two of his immediate relatives, stand by the side of a large stone tank with broad flights of steps and flanking towers, which be restored and brought into its present shape. This is esteemed sacred and commonly called Bhanokhar, that is, the tank of Brikha-bhan, Radha's reputed father. In connection with it is a smaller reservoir, named after her mother Kirat. On the margin of the Bhanokhar is a pleasure-house in three stories, known as the Jal-mahall. It is supported on a series of vaulted colonnades which open direct on to the water, for the conve nience of the ladies of the family, who were thus enabled to bathe in perfect seclusion, as the two tanks and the palace are all enclosed in one courtyard by a lofty bastioned and embattled wall with tower-like gateways [9] Besides these works, Rup Ram also constructed two other large masonry tanks, one for the convenience of a hamlet in the neighbourhood, which he settled and called after his own name Rup-nagar; the second on the opposite side of the town, in the village of Ghazipur, is the sacred lake called Prem Sarovar, which he faced with octagonal stone ghats. Opposite the latter is a walled garden with an elegant domed monument, in the form of a Greek cross, to his brother Hem-raj.

Contemporary with Rup Ram, two other wealthy families resided at Barsana and were his rivals in magnificence. The head of the one family was Mohan Ram, a Lavania Brahman; and of the other Lalji, a Tantia Thakur. It is said that the latter was by birth merely a common labourer, who went off to Lakhnau to make his fortune. There he became first a harkara, then a jamadar, and eventually the leading favourite at court. Towards the close of his life he begged permission to return to his native place and there leave some permanent memorial of the royal favour. The Nawab not only granted the request, but further presented him with carte blanche on the State treasury for the prosecution of his designs. Besides the stately mansion, now much dilapi dated, he constructed a large baoli, still in excellent preservation, and two wells, sunk at great expense in sandy tracts where previously all irrigation had been impracticable.

The sacred tank on the outskirts of the town called Priya-kund, or Piri- pokhar, was faced with stone by the Lavaniyas. Who are further commemorated by a large katra, or market-place, the ruins of the vast and elaborate mansion where they resided, and the elegant stone chhattris at the foot of the hill. They held office under the Raja of Bharat-pur, and their present representative, Ram Narayan, is now a Tahsildar in that territory.

Barsana had scarcely been built, when, by the fortune of war, it was des troyed beyond all hope of restoration, as has already been related in Chapter II of this memoir, page 42. As if this blow were not enough, in the year 1812 it sustained a further misfortune, when the Gaurua Thakurs, its zamindars, being in circumstances of difficulty and probably distrustful of the stability of British rule, then only recently established, were mad enough to transfer their whole estate to the oft-quoted Lila Babu for the paltry sum of Rs. 602 and the condi tion of holding land on rather more favourable terms than other tenants. The parish now yields Government an annual rental of Rs. 3,109 and the absentee landlords about as much, while it receives nothing from them in return. Thus the appearance now presented by Barsana is a most forlorn and melancholy one.

The hill is still, to a limited extent, known as Brahma-ka-pahar or Brahma's hill: and hence it may be inferred with certainty that Barsana is a corruption of the Sanskrit compound Brahma-sanu, which bears the same meaning. Its four prominent peaks are regarded as emblematic of the four-faced divinity, and are each crowned with some building; the first with the group of temples dedicated to Larli Ji, the other three with smaller edifices, known respectively as the Man-mandir, the Dan-garh and the Mor-kutti. A second hill, of less extent and elevation, completes the amphitheatre in which the town is set, and the space between the two ranges gradually contracts to a narrow path, which barely allows a single traveller on foot to pass between the shelving crags that tower above him on either side. This pass is famous as the Sankari-khor, [10] literally ‘the narrow opening,’ and is the scene of a mela (called the Burhi Lila) on the 13th of the month of Bhadon, often attended by as many as 10,000 people. The crowds divide according to their sex and cluster about the rocks round two little shrines, erected on either side of the ravine for the temporary reception of figures of Radha and Krishna, and indulge to their heart's content in all the licentious banter appropriate to the occasion. At the other mouth of the pass is a deep dell between the two high peaks of the Man-Mandir and the Mor-kutti, with a masonry tank in the centre of a dense thicket called the Gahrwar-ban. A principal feature in the diversions of the day is the scram bling of sweetmeats by the better class of visitors, seated on the terraces of the ' Peacock Pavilion' above, among the multitudes that throng the margin of the tank some 150 feet below.

The essentially Hindi form of the title Larli, equivalent to the Sanskrit Lalita, may be taken as an indication of the modern growth of the local cultus. Even in the Brahma Vaivarta, the last of the Puranas and the one specially devoted to Radha's praises, there is no authority for any such appellation. In the Vraja-bhakti-vilisa the mantra, or formula of incantation which the pril grims are instructed to repeat, runs as follows:

Lalita-sanyutam krishnam sarvaishu sakhibhir yutam Dhyaye tri-veni-kupa-stham maha-rasa-kritotsavam.

NAND-GANW—population 3,253—as the reputed home of Krishna's fosterfather, with its spacious temple of Nand Rae Ji on the brow of the hill over-looking the village, is in all respects an exact parallel to Barsana. The dis tance between the two places is only five miles, and when the kettle-drum is beaten at the one, it can be heard at the other. The temple of Nand Rae, though large, is in a clumsy style of architecture and apparently dates only from the middle of last century. Its founder is said to have been one Rup Sinh, a Sinsinwar Jat, and it has an endowment of 826 bighas of rent-free land. It consists of an open nave, with choir and sacrarium beyond, the latter being flanked on either side by a Rasoi and a Sejmahall, i.e., a cooking and sleeping apartment, and has two towers, or sikharas. It stands in the centre of a paved court-yard, surrounded by a lofty wall with corner kiosks, which command a very extensive view of the Bharat-pur hill and the level expanse of the Mathura district as far as Gobardhan. The village, which clusters at the foot and on the slope of the rock, is, for the most part, of a mean description, but contains a few handsome houses, more especially one erected by the famous Rup Ram of Barsana. With the exception of one temple dedicated to Manasa Devi all the remainder bear some title of the one popular divinity, such as Nar-sinha, Gopi nath, Nritya-G- opal, Giridhari, Nanda-nandan, Radha-Mohan, and Jasoda nandan. This last is on a larger scale than the others, and stands in a court-yard of its own, half way up the hill. It is much in the same style and apparently of the same date as the temple of Nand-Rae, or probably a little older; an opinion which is confirmed by its being mentioned in the mantra, which runs as follows —Yasoda-nandanam bande nanda-grama-vanadhipam. A flight of 114 broad steps, constructed of well-wrought stone from the Bharat-pur quarries, leads from the level of the plain up to the steep and narrow street which termi nates at the main entrance of the great temple. The staircase was made at the cost of Babu Gaur Prasad of Calcutta, in the year 1818 A. D. At the foot of the hill is a large unfinished square with a range of stone buildings on one aide for the accommodation of dealers and pilgrims, constructed by Suraj Mall's Rani, the Rani Kishori. At the back is an extensive garden with some fine Khirni trees, the property of the Raja of Bharat-par. They are, however, gradu ally disappearing, one by one every year, and no attempt is made to replace them. A little beyond this is the sacred lake now called Pan Sarovar, and supposed to be the pool where Krishna used to drive the cows to `water' (pan). It is a magnificent sheet of water with noble masonry ghats on all its sides, the work of a Dowager Rani of Bardwan in 1747 A. D. It measures 810 feet by 378, and therefore covers all but six acres. It is said to be designed in the form of a ship; but the resemblance is not very apparent to an uninformed observer. This is one of the four lakes of highest repute in Braj; the others being the Chandra-sarovar at Parsoli by Gobardhan, the Prem-sarovar at Ghazipur near Barsana, and the Man-sarovar at Arua in the Mat pargana. On its margin is a little temple of Bihari, which bears on its front the following inscription: Sri Radha Gobind, Sri Gadadhar Chaitanya, Sri Pavan-sarovar Kunj Srimati Rani Rasyesvari Raja Kirtichand ki mata Sri Raja Tilok Chand ji ki dadi ji raj sube Bangala Baradman Sri Sanatan Rup ki jaga men banawe Gumashta Sri Saphalya Ram Das, Gokul Das sambat 1805. The following commemorates some later repairs in 1849; Sri Nandisvar men Chhajju zamin dar ki patti men san 1155 sal, mah bhadra sudi men, Sri, Pavan wa kunj paki bhayi, memar Mohan Lal, Chet Ram. Both these inscriptions are noticeable, since, in spite of their modern date, they preserve the old and now entirely obsolete name both of the village, Nandisvar (i.e., Mahadeva) instead of Nanda, and also of the lake, Pavan, 'the purifying,’ instead of Pan, 'to drink.' Near the village is a kadamb grove, called Udho ji kit kyar, and, according to popular belief, there are within the limits of Nand-ganw no less than fifty-six sacred lakes or kunds; though it is admitted that in this degenerate age all of them are not readily visible. In every instance the name is commemorative of Krishna and his friends and their pastoral occupations.

Like Barsana and so many others of the holy places, Nand-ganw is part of the estate of the representatives of the Lala Babu, who, in 1811 A. D., acquired it for a merely nominal consideration from the then zamindars. One reason for their readiness to part with it is probably to be found in the fact, which has only recently come to my knowledge, that their title was a very questionable one. For the Pujaris of the temple have in their possession a sanad dated the 30th year of Alam Shah giving the whole of the village to their predecessors Paramanand and Ramkishan and their heirs in perpetuity.

If the few squalid buildings which at present disfigure the square at the foot of the hill were removed, and replaced by a well, or temple, or other pub lic edifice, and the line of shops completed on the other side, an exceedingly picturesque effect might be secured at a comparatively small cost. But it is needless to expect any local improvements from the absentee landlords, while the inhabitants are too impoverished to have a thought for anything beyond their daily bread.

The above sketch of two comparatively unimportant places affords a good illustration of a curious transitional period in Indian history. After a chec quered existence of five hundred years, there expired with Aurangzeb all the vital energy of the Muhammadan empire. The English power, its fated sue cessor, was yet unconscious of its destiny and all reluctant to advance any claim to the vacant throne. Every petty chieftain, as for example Bharat-pur, scorning the narrow limits of his ancestral domains, pressed forward to grasp the glittering prize, and spared no outlay in the attempt to enlist in his ser vice the ablest men of any nationality, either like Samru to lead his armies in the field, or like Rup Ram to direct his counsels in the cabinet. Thus men, whatever their rank in life, if only endowed by nature with genius or audacity, rose in an incredibly short space of time from obscurity to all but regal power. The wealth so rapidly secured was as profusely lavished; nor was there any object in hoarding, when the next chance of war would either increase the treasure ten-fold, or transfer it bodily to a victorious rival. Thus, a hamlet became in one day the centre of a princely court, crowded with magnificent buildings, and again, ere the architect had well completed his design, sunk with its founders into utter ruin and desolation.

References

- ↑ .In Christian mysticism 107 is as sacred a number as 108 in Hindu. Thus the Emperor Justiman's great church of S. Sophia at Constantinople was supported by 107 columns, the number of pillars in the House of Wisdom.

- ↑ In devotional literature manasi has the sense of 'spiritual,' as in the Catholic phrase ' spiritual communion.' Thus it is related in the Bhakt Mala that Raja Prithiraj, of Bikaner, being on a journey and unable to visit the shrine, for which he had a special devotion, imagined himself to be worshipping in the temple, and made a spiritual act of contemplation before the image (murti ka dhyan manasi karte the). For two days his aspirations seemed to meet with no response, but on the third he became conscious of the divine presence. On enquiry it' was found that for two days the god had been removed elsewhere, while the temple was under repair. He then made a vow to end his days at Mathura. The emperor, to spite him, put him in command of an expedition to kabul; but when he felt his end approaching, he mounted a camel and hastened back to the holy city and there expired.

- ↑ The estate is divided into twenty-four bats or shares, allotted among seventeen different families. It appeared that all were agreed as to the distribution, with the exception of one man by name Narayan, who is addition, to his own original share, claimed also as sole representative of a shareholder deceased. This claim was not admitted by the others, and the zamindars continued to pay the revenue as a deposit into the district treasury, till eventually the muafldars concurred in making a joint-application for its transfer to themselves.

- ↑ In the garden attached to this chhattri the Maharaja has a house, where he stays on his visits to the town; but at all other times it is most obligingly placed at the disposal of European visitors.

- ↑ Hans-ganj, on the bank of the Jamuna, immediately opposite Mathura, was founded by this Rani. In consequence of a diversion of the road which once passed through it, the village is now that most melancholy of all spectacles, a modern ruin though it comprises some spacious walled gardens, crowded with magnificent trees.

- ↑ The ten names-whence the title Das-nami-are tirtho, asrama, vana, aranya,sarasvati, puri, bharati, giri, parvata, and sagara, one of which is attached to his personal name by every member of the order.

- ↑ Both these interesting places, as also Baladeva, are entirely omitted by Dr. Hunter in his Imperial Gazetteer, and all the places in the district that he does mention are described with remarkable inadequacy and inaccuracy, Apparently his test of the importance of any locality is his own personal connection with it: hence the disproportionate length of some of the Bengal articles.

- ↑ It appears that Barsana was an occasional residence of Madho Rao Siindhia; for a tresty of his with the company, regarding trade at Baroch, dated the 30th of September, 1785, was signed by him there, as also the supplementary article dated the following January.

- ↑ Both the house and Bhanokhar hare been considerably damaged by the new proprietor, who has removed many of the larger slabs of stone.

- ↑ A similar use of the local form khor, for khol, may be observed in the village of Khairs, where is a pond celled Chinta-Khori Kund, corresponding to the more common Sanskrit compound Chinta-harana.